- Home

- Mike Scardino

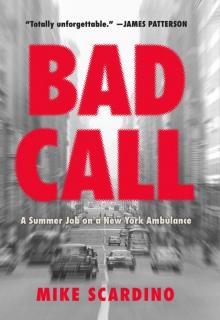

Bad Call Page 10

Bad Call Read online

Page 10

I have also gotten really good at feeling sorry for myself. Poor me. Tough shit.

Anyway, it’s a wonderful day today. One of those matchless New York days that presage the best time of the year anywhere on earth—autumn in the Big Apple. The air is crisp and it’s in the low seventies and there’s a nice breeze. What could go wrong on a day like this. What would have the nerve to go wrong on a day like this.

Here’s what. A call. Man down in Woodside. It’s a rush. I’m on with Eddie all week. Eddie is a law student at Fordham and very smart. He’s a nice guy, but he can get a little edgy, so I tread lightly.

He reads a lot—law books, of course. He’s going to school full-time while he works on the ambulance full-time. Carrying work and school is heroic, in my book.

This week, Eddie and I are on days, which is unusual for him. Nights sync up better with his studies. He has his nose in a book as we get the call. I really admire his study habits. More than admire. I’m in awe and a little jealous. How does he do it. Maybe I can broach the subject with him one of these days. It will have to be soon, with back-to-school on the horizon.

We’re in 433 with the lights on and the siren going. Eddie loves the siren. I can’t see why. What a racket, right over our heads. But it’s not that far a ride, so what the hell.

We’re in a small neighborhood, an enclave, really, very middle class for this area, which translates into upscale compared with other locations in Woodside. It’s a private house, in a long row of similar houses, the kind with very narrow driveways between them. My guess is these houses were built no later than the twenties, when the widest cars were around the width of a Model A. The cops are here already.

Where is it.

In the garage.

The garage is all the way down at the end of the driveway. I don’t think we can make it with the ambulance—the mirrors are enormous and probably add at least three feet to our width. Eddie agrees. So we park at the curb, haul out the stretcher, and start rolling it down the driveway.

This looks just like our garage at home in Bayside. Has to be the same vintage. It’s a wood-frame building with barn doors, and it has seen better days. It needs a new paint job badly, and the walls are buckled out at the bottom in places. Inside, it is jam-packed with power tools, cans of oil and solvents, yard tools, bikes, and other important junk. Again, just like ours.

There are six of us on the scene. Eddie and me, two policemen, the patient, and one other man, who turns out to be the patient’s friend and neighbor. The patient is sitting on the concrete floor of the garage. There’s blood but not a whole lot. Mr. Neighbor has taken care of that.

The patient’s pulse and color are good, but one of his legs is totaled, a complete disaster. It will have to come off. Jesus, it’s mostly off already. All they’d have to do is debride it, trim it up, make a flap, and close. I have rarely seen such an injury on a living patient. He’s not talking but doesn’t seem to be in a whole lot of pain. I’m taking the information on my pink sheet while one of the cops tells us the story he’s gotten from Mr. Neighbor.

Apparently, against the admonitions of manufacturers, craftsmen, and machine workers all over the world, our patient thought he would save a few bucks and craft a homemade grindstone—to mount on a high-speed electric bench motor. This is a serious piece of equipment and deserves some real respect. My father has one of these at his gas station, and he respects it very much. None of the stones he uses is homemade.

The problem with a stone that isn’t made with material specifically designed for one of these powerful electric motors is that the centrifugal force generated can sometimes cause it to disintegrate explosively, with really dire consequences. It is one of these dire consequences that we’re witness to on this beautiful pre-autumn day in Queens.

The cop continues. Apparently Mr. Neighbor was in his yard, about an arm’s length away, when the stone blew apart. This was a big stone. A piece the size of a healthy wedge of pie went flying into the patient’s leg at a very high speed. Like a piece of stone shrapnel fired from a cannon. This pie wedge smashed the man’s thigh to pulp, splintering the femur, tearing apart muscles, and ripping open blood vessels. How it missed the femoral artery is anyone’s guess and has to be a minor miracle. If it had not missed this vessel, this man would be DOA now. No question.

Almost immediately after the explosion and impact, Mr. Neighbor sprang into action. He grabbed some electrical cord and fashioned a tourniquet to stop the bleeding. I am looking at the wire—I can hardly see it, it is dug in so deep. Mr. Neighbor has applied it so tightly that it is embedded inches into the crook between the leg and groin. I’m trying to get a finger under it. Can’t do it. I try to get a pair of bandage scissors under it. Can’t do that, either. I don’t think I will try the wire cutters, which are right here in the shop. The wire is in there too deep to get any purchase with something that blunt. Just as well.

No point in taking off the tourniquet anyway. The bleeding has stopped. I mean, it has really stopped. There is no circulation whatsoever in this leg. This leg is history. Thank you, Mr. Neighbor.

Mr. Neighbor didn’t stop with the tourniquet, though. Oh no. Who knows why people do the things they do. There’s no explaining it. In some sort of self-styled First-Aider Frenzy, he decided the stone pie wedge needed pulling out, as they do with all those arrows in the westerns. In doing that, he has avulsed the contents of the patient’s thigh. I’m staring at them all now. The contents. This incredible mess he has made.

This well-meaning goddamn dumb-ass meddlesome ignorant son of a bitch.

When Mr. Neighbor pulled out the pie, he pulled out most of the stuff inside the thigh with it. And here it all is—pie wedge, bone shards, blood vessels, fat, tendons, muscles—an alfresco anatomy lesson laid out for our inspection. All lying neatly in the crotch of a soon-to-be amputee, on the concrete floor of a beat-up garage workshop in Woodside.

I’m wondering if this man’s leg could have been saved if his neighbor had not intervened. I know there’s no way I can know this. What I do know for sure is that a couple of tragically dumb guys really screwed up here.

I also know for certain that school starts next week. Hallelujah.

To All a Good Night

I can remember the exact night I stopped loving Christmas. I was working with Pop at the gas station, outside pumping gas. It was bitterly cold and windy. I think the wind chill, if not the actual temperature, was in the single digits. It wasn’t much warmer inside, but at least there was no wind in there. We worked until after 8:00 p.m. as usual and then went home. I was exhausted and I know he was as well. I was too exhausted to enjoy Christmas, and I haven’t felt the same about it since.

I know there are occupations where people have to work on Christmas Eve. And Christmas Day as well. And other sacrosanct holidays. But we didn’t have to stay open until 8:00 p.m. to pump gas.

The ambulance business is different, of course. Like the diner signs say: WE NEVER CLOSE.

Since I’m the primary relief guy at St. John’s, it didn’t take them long to start calling the house during the holidays, knowing I’d probably be there, back from school on Christmas break. By didn’t take them long, I mean my very first Christmas home after starting the job. Because all the guys want to take as much time off for the holidays as they can, I am in constant demand.

The way I feel about Christmas, it doesn’t really matter to me if I work or not. So I work. Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, New Year’s Eve, New Year’s Day. The days and nights in between. Makes no difference to me.

I’m learning that working in the cold weather is dramatically different from working during the warm months of summer. For one thing, there are generally fewer calls. People aren’t out and about as much. There seem to be fewer serious traffic accidents. The cold weather appears to even out people’s temperaments. There are fewer assaults, fewer fights, and, I believe, fewer homicides. I’m not sure if statistics will bear this out. I’m just going by obser

vation.

There are more of other kinds of calls. Lots of heart attacks and strokes brought on by shoveling snow. Despite seasonal warnings, year after year. The proud, recalcitrant elderly go outside and shovel and come inside and die. It’s a shame people are so stubborn, but who wants to admit they can’t do what they used to do.

There are lots of minor accidents. Most of them are fender benders caused by the slippery conditions. One time we had to stop counting at thirty accidents, all on overpasses and cloverleafs up by La Guardia. The ramps had turned to solid ice, and about every fifty feet there was a car that had slid into the guardrail and become immobilized. Miraculously, not a single person was hurt.

How did we manage to negotiate those ramps in a top-heavy ambulance with a manual transmission, numb steering, no snow tires, no four-wheel drive, and not even positraction. Beats the hell out of me. Since coming to work for St. John’s, I have been amazed at the driving skills of some of the men I work with—and that is during the summer.

Watching them drive in winter, on high-crowned streets paved with Belgian blocks and glazed with ice, is always an awesome—and sometimes terrifying—experience.

Add to that the eves, when there is generously spiked eggnog hidden away in the ER treatment room, and you have the potential for some invigorating sleigh rides, indeed. But so far there have been no incidents or accidents when I’ve worked winters. That’s usually a desirable thing on an ambulance.

Tonight is the night of Christmas Day, and things are pretty quiet. It’s snowing heavily, and I don’t expect much action out there, but I may have spoken too soon. We’ve got a call—it’s a man down, struck by a car on the Grand Central Parkway right near La Guardia.

A pedestrian crossing the Grand Central at night on Christmas in a blizzard. Oh why.

Possible DOA and it’s a rush. I cannot understand how it can be both a DOA and a rush at once, but that’s the way some of these calls come in. Must be Central’s version of me doing the dispatching this evening—the holiday replacement guy.

I’m partnered up with Leroy tonight. I’ve known him as a customer at Dad’s gas station since before I started working at St. John’s. I don’t ride with Leroy a lot and don’t have much of an opinion of him one way or another, except that I’m a little bit afraid of him. He is a giant of a man and strong beyond belief. He has to be the most powerful guy we work with, by a big margin.

Leroy is not real talkative, and it can be very hard to read his moods. Impossible, actually. Maybe there’s nothing there to read. He has a look of permanent consternation on his face, like someone who thinks he may have been insulted in some manner but can’t quite figure out how. Not really angry; more like pre-angry. Maybe he doesn’t have moods. Maybe it’s just mood. The Leroy Mood.

Think morose Li’l Abner with a Queens accent, and you have a good approximation of Leroy.

Sometimes we ambulance guys get involved in a bit of roughhouse grab-ass out in the yard when things are slow and we’re feeling a little zestful. I wuz a-rasslin’ around with Leroy, and he lifted me up two feet off the ground as if I weighed nothing, as opposed to two hundred eleven pounds. This effectively dissipated my momentary zestiness and was quite sobering. I would never, ever want to get on Leroy’s bad side. That is for sure. Less sure is how to know when or if I am doing that. I will always be careful with this man.

But tonight we’re in a festive frame of mind—at least I am, as festive as one can be when one hates the holidays and is teamed up with a Grinch like Leroy, driving at heart-stopping speed in blinding snow on the way to a rush DOA. You have to live in the moment, they say. Last night’s leftover ER eggnog tastes just as good tonight and has created a nice, warm sensation in the bottom of my stomach, and it feels pretty good.

I have to admit the snow is beautiful, in and of itself—and better than that, it covers up some of the ugliness as we make our way from Elmhurst through Astoria to the Grand Central Parkway.

I guess snow can make almost anything look good, like beautiful icing on a crappy cake. Anything but the roads, that is, when you have to be out driving on them. They are getting worse by the minute, and so is the visibility. I see flashing lights up ahead, barely, and it looks like we’ve found our DOA.

There is very little traffic as we get out and make our way over to the scene. I’m looking for a victim, and I find him, lying faceup under a blanket. That blanket, in turn, is under a fast-accumulating blanket of snow. He’s lying about twenty feet behind the car that took his life. He and the car are both in the right-hand lane. I need to check out the poor guy under the blanket to make sure he’s beyond assistance.

There are no vital signs whatsoever. He is very dead. If he had been alive, letting him lie there on the cold, snowy road would have probably finished the job that the car started. No blanket could have kept him from going into shock almost immediately. I hope that wasn’t what happened. I have to imagine death was virtually instantaneous, even though it’s hard to figure out at a glance exactly what killed him. Just putting it all together, I’d say death was due to being hit by a car going forty to fifty miles per hour on the GCP. That’s just my expert opinion. I know Leroy must have an opinion, but he’s very private about things like that. Opinions.

The driver is a thirtyish white male. He’s understandably shaken up and sitting in his car in the driver’s seat sideways with the door open. He wants to tell me what happened, and I’m more than willing to listen, even though the wind is picking up and we really should be moving along.

He’s an off-duty cop. He tells me he hasn’t had anything to drink, despite the fact that this is Christmas Day. I believe him. There’s not a hint of alcohol on his breath. Speaking of his breath, I think he may hyperventilate if he doesn’t ease up a bit. He’s that upset. Try to breathe deeply through your mouth. Slow, deep breaths. That’s good. Just like that.

I’ll bet he’s been called to respond to his share of traffic fatalities. But it’s so different when you’re in the play and not the audience. He starts speaking, rapidly: Do you know that a lot of the workers at La Guardia cross over this section of the road as a shortcut to get to work, he asks me. I actually do know that, but I tell him no. He thinks that’s who the victim is. I almost didn’t stop. I thought I hit a cardboard box or something; it didn’t feel like nothing. I could hardly see from the snow. I wasn’t even going that fast. I didn’t know what had happened until I looked in my mirror and saw him come flying down behind me. I must of knocked him clear over my car. I don’t know, maybe he died when he hit the ground and the impact didn’t do it. Do you think. I stopped as soon as I saw what happened. Oh Christ. Oh Jesus Christ.

Judging from the almost total lack of damage to his car, I could believe that the impact with the car may not have killed the man under the blanket. Judging from the proximity of the body to the car, I believe the officer stopped as quickly as he said. I’m trying to console him as well as I can by simply telling him the truth and not just what I think he’d like to hear. That it’s a blinding snowstorm and nobody would expect a pedestrian to be here and he stopped as soon as he knew what had happened and it’s not his fault. But it still happened. Nothing I could say would change that.

We have to take him away now. The victim, that is. Although for a moment there I thought we might have to take the driver if he didn’t calm down. It wouldn’t be the first time that a driver involved in a fatal accident had a coronary at the scene. And it wouldn’t be the first time one of those proved fatal.

Leroy and I are going to lift the dead man by his clothing and put him on the stretcher. Leroy has him by the jacket, and I have him by the pants legs. When we lift him up, both of his legs fall out of his trousers, thump, thump, onto the snowy highway.

Both have been neatly amputated in exactly the same spot, right at the knee.

Well, this was not caused by the fall. It had to be from the impact with the car. How his legs stayed put in his trousers as he catapulted over the vehicle

is anyone’s guess. At least we don’t have to go hunting for them in the snow. I’m trying to figure out if this sounds callous or not. I hope I never get callous about these things. But you have to be practical; you can’t come back without all the pieces, and sometimes it’s not that easy to find them.

I quickly put the legs on the stretcher, and we re-cover the body and parts with the blanket. I don’t want the cop to see this. He’d know then it was his car that probably killed the man, instead of the impact with the road. I personally can’t see how it would make a difference, but I think it would to him. So why let him see this if he doesn’t have to.

Why spoil his Christmas any more than it is already.

Poor guy. There won’t be a single Christmas for the rest of his life when he won’t remember this event. And the victim—he should never have tried to cross the Grand Central on foot, much less in a blinding snowstorm. But still, it’s a tragedy that he’s dead. Assuming he has a family, this will ruin their Christmases for the rest of their lives, too.

I can’t help feeling very sad for these two men and their families, and it’s making me feel bad about Christmas all over again, starting to reverse my dim hopefulness that I might grow to love it once more. Not only that, but now I feel guilty about being so sorry for myself for having to work that Christmas Eve at Pop’s gas station. What was that, compared with this.

The snow is really coming down now. Very heavy. Just not heavy enough.

The Worst Thing You’ve Ever Seen

It’s the start of my third summer at St. John’s. Today I’m on with Pete, the boss. Hooray. I’m working days this week and so is he, and because I don’t have a car yet, he picks me up at home (we both live in Bayside) and he drives me to work. Pete and Pop conspired to get me the job on St. John’s, so Pete thinks I owe him big-time and he never lets me forget it, if not overtly, then by his attitude. I’m frankly surprised he’s never asked for some kind of rebate for his beneficence.

Bad Call

Bad Call