- Home

- Mike Scardino

Bad Call Page 14

Bad Call Read online

Page 14

Here comes Tony at full twitch. He’s waving at me frantically, the only way he waves, to come with. He’s found a live one. There’s so much crap on the street I have to lift up the stretcher and carry it by hand, over the car pieces and hoses and bodies and body parts. Tony says this woman is alive. Mind if I check. Good for you, Tony. She’s still with us. She’s unconscious but definitely alive, though she has severe lacerations and may have spinal or internal injuries, always a possibility. No time to go back up for the backboard, though.

Tony and I are poised to lift her onto the stretcher when two firemen appear and proceed to usurp her berth on the stretcher with a man who is quite obviously dead.

Whoa, whoa, whoa, you guys, this man is dead.

No, he isn’t.

Yes, he is. And there they go.

In the heat of the moment, our stretcher has been taken away from a woman who might have made it, to be put into use for the pointless transportation of a dead man. Tony and I have no choice but leave the woman on the ground and try to keep up with the firemen who are slipping and sliding with the stretcher up the grassy hill. Lady, I’m sorry. Please forgive us. Please forgive them. It’s all we can do to scramble up the hill and catch up with the firemen at the wall, where they’re waiting for us to climb over so they can pass us the stretcher.

I feel sick. I hope to God someone else will pick up the woman and get her to a hospital in time. Maybe they won’t be able to save her, but she deserves a shot, at least. At least a shot.

We’re supposed to save lives, not operate the River Styx Express. I know it’s not our fault. Is it the firemen’s. It’s not for me to say. They made a command decision, and that’s that. They’re trained to be decisive under the worst circumstances. Circumstances where you do not get a chance to second-guess yourself. I wouldn’t want their job for a million bucks, not that I could do it anyway. They do incredible things. This time, they made a mistake. It happens. It’s the Fog of War.

Take it easy, for Christ’s sake, Tony, slow down. We don’t need to get killed today, too. Slow down, you goddamn little rat bastard. Nothing I am saying to Tony has any effect whatever. It never does.

Now this is too freaking much. Just too much. They’re giving us a hard time at Elmhurst General for bringing in a dead man. Hey, St. John’s, they’re telling us, you got us mixed up with Queens General. This guy goes in the morgue.

No shit.

I don’t know if I have the energy to go through the story. I don’t. I’m insisting he’s DIT—died in transit. I don’t think they believe me. I wouldn’t, either. I don’t care. He has stopped bleeding for a while, and we all can clearly see that. His lacerations have started to dry out and crust over on the edges.

Maybe we should have taken him to the morgue, but EGH is closer—and we have to return to the scene. Maybe we’ll be able to pick up someone whose life can be saved. Maybe it will be the woman we left in the sun on the pavement on the Connecting Highway. Maybe, maybe, maybe.

Look, we’d love to stay and talk but we have to run.

There’s more where he came from.

The Sight of Blood

Blood never bothers me much. I know there are those who faint at the sight of it, although I haven’t seen that. But I know personally someone who has fainted just hearing it discussed.

Last fall when I got back to Nashville, I was having Sunday brunch at the Burger King across West End Avenue from my dorm with one of my best friends, Dave. He had brought along another guy, named Ry, whom I had never met before, and we three sat down to our Whoppers, large fries, and shakes to discuss our summers and fuel up for the start of classes the next day.

As usual, Dave wanted to hear about my summer working for St. John’s. Dave and I are both premeds. He’s brilliant, a chemistry major. He’s brilliant and he actually works hard studying. He will be a doctor. I won’t. I could say this job has ruined me for it. I could say I’m psychologically trashed. I could say a lot of things. The truth is I don’t want to be around the injured, sick, and dying any more than I can help it. I just don’t want that to be my future. It’s also true that I have always had terrible study habits. And finally—I’m just not that smart. I believe you have to be uniquely gifted to master organic chemistry, calculus, advanced biology, and physics. Dave is. I’m not.

But ambulance stories have little to do with medicine, after all.

Ambulance stories are campfire tales. They have the power to disgust or frighten or sadden or even exhilarate both the teller and the listeners. In this case, me and Ry and Dave.

I was sitting across from Ry as we were eating, and I happened to be telling a story about a call we had over the summer, a massive accident involving multiple cars and several DOAs. The street was flooded in blood. The blood was deep at the curb. Several inches. So deep that before I knew it, it had washed over the tops of my shoes, soaking my socks and my feet.

Normally we have a change of shirt and pants at the hospital in case we get messy on a call. I don’t believe any of us would have ever thought to have another set of shoes and socks to wear. When I got back to St. John’s after this call, I squooshed myself through the ER, past wide-eyed patients, into the bathroom, took off my shoes and poured the residual blood into the toilet, wrung out my socks, and dried off everything as well as I could with paper towels, which I threw without thinking into the toilet. Rather than risk backing up the toilet, I didn’t flush. I often wondered what the next guy in there thought had happened.

Despite my best cleanup efforts, my footwear was a bloody, soggy mess for the rest of my shift. Several hours.

While I was recounting this event, I noticed Ry had stopped in midbite. He was holding his Whopper in both hands with his elbows on the table and his mouth partly open, but he wasn’t chewing, even though his mouth held an enormous burger bolus.

His face was dead white and brilliant with sweat. For just a moment, I thought he was having a heart attack. He was staring straight at me when he went down, sideways, onto the Burger King floor. Whopper, fries, shake, tray, and all. This was a first for me. I had never seen anyone faint at the sight of blood, but now I’d seen someone faint at the sound of it.

I felt horrible. And yet fascinated at the same time. Ry was fine. It turned out that he also fainted at the sight of hypodermic needles, which I couldn’t have known. I apologized and secretly hoped we could still stay friends. And we have.

Blood is fascinating. It has so many forms, from black and viscous to thin and runny. It can be as slippery as oil and then turn sticky. It can congeal like gelatin and then turn dry and crusty. I can’t think of any other liquid that has the same complex properties. It also smells peculiar. I’ve heard the smell described as metallic, and I think I’d agree with that.

When I was in grammar school, I briefly studied the bugle. I was fascinated by the curious smell my fingers took on after contact with the tarnished brass (it was a used bugle). That’s how blood smells to me. Like the smell of brass on fingers.

It can smell a lot worse than that.

Lenny and I were hanging out in the ambulance on a blistering day in the yard, hoping things would stay slow enough to let us catch a catnap. Things were slow enough, but we couldn’t sleep. Something smelled funny. So funny that we both decided to check it out.

We went in the back, and it was clean. Not eat-off-the-floor-clean like an operating room, but clean enough. Nothing visibly wrong, but the smell was definitely coming from the back. It smelled really bad, but neither one of us could put a finger on it. We opened the bench. Nothing there. Lenny looked at the floor. There was just the slightest brick-red line of color around the hatch in the floor, under which there’s a dry sump where we store all kinds of extra supplies, mainly Kerlix, bandages, gauze, and splints padded with gauze. He and I looked at each other and shrugged, and then I opened the hatch.

Oh my God.

All of our highly absorbent gauzy materials were completely soaked with what looked like ga

llons of rotting blood. I know it couldn’t have been gallons. I’m exaggerating, of course. Max for an adult is around ten pints. Every ounce of which looked like it made its way around the hatch and into the sump to be sucked up by our yards and yards of now-contaminated bandages. It all had to be cleaned out, and it would take a good while to do that.

Lenny and I went inside to call the ambulance out of service and try to find out what happened. We did.

It was a simple story. They had a bleeder overnight. It was dark. They mopped out the ambulance as well as they could without taking it out of service, but of course they had no idea that so much blood—that any, really—had seeped down below the floor. I say seeped. It was more like someone had opened up the hatch and squeegeed it all in. It’s hard to imagine how much of it was left for them to mop up off the floor. Or how much was left in the poor patient.

It took Lenny and me the better part of two hours in the midafternoon sun to take out the stinking, sopping, blood-drenched materials piece by piece, then soak up the remaining decomposing blood, then wash out the sump by hand and mop the floor and back of the ambulance and let the sump dry out sufficiently to fill it again with new materials. It had to be perfectly dry, or there would be problems. (Employee memo to St. John’s: Install drain in sump.)

It still didn’t bother me all that much, except for that smell.

I’ve been covered with blood after calls. As I say, I usually have a spare uniform on hand, but sometimes I forget to bring one, so I have come home with blood on my clothes. I always try to hide it from Mom and Dad and my sisters, but once in a while they’ll see it and be repulsed. Excuse me, did you guys not know I was working on an ambulance.

It just so happens we’re on a rush call right now, and it’s a bleeder. Man stabbed. It’s about 2:30 on a Sunday morning, and Jose and I both guess there’s been some kind of bar brawl or altercation (love that euphemism) that led to blood being shed in anger. Could be anything, really.

It’s all out in the street. Very theatrical, directly under the ghastly light of a mercury-vapor streetlamp. The cops are here, and there’s a kid with a bloody T-shirt wrapped around his right hand. The shirt is soaked, and it must be his, since he’s topless. Nobody else is around. He has to be freezing with his shirt off—it’s chilly tonight and we don’t want to have him going into shock, so we need to be quick about this.

I’m unwrapping the T-shirt and there it is—a deep gash right across his palm from side to side, to the bone. Clearly a defensive wound. He says somebody cut him with a bottle. It was a broken bottle, he adds. Uh-huh, I say. I figured as much.

He’s bleeding heavily, so first order of business is to get that stopped. I hand him a wad of gauze to squeeze and tell him to hold up his arm as high as he can while he’s squeezing. The gauze gets soaked quickly, and the bleeding is unabated. Never had a hemophiliac before—could this be my first, I wonder.

I have his elevated arm in my left hand, and I’m starting to bandage his wound with my free hand. Is that too tight. He says nothing. Well, too bad anyway, it has to be tight.

While I’m working, a steady stream of his blood is flowing down his arm, over my hand, and onto my bare arm, down to the inside of my elbow. Even though it’s chilly, we’re wearing our summer short sleeves. And, of course, we never wear gloves except on maternity calls.

Something is a little unsettling. It’s his blood. The way it feels.

It feels good. Warm as it is. Running down my hand and arm on this unseasonably cool night. Nice and warm. It feels really good.

God help me. What the hell is happening to me.

Done

My parents thought working on the ambulance at St. John’s would be a great job for me as a premed student.

I don’t know how to tell them that I think working on an ambulance has turned me against medicine as a career.

Very soon it will be out of my hands anyway, because my grades are just not good enough to get into any decent medical school. To make things worse, I’m burned out. At twenty. Many of the things I’ve seen, the really awful things that keep me up at night, have nothing remotely to do with the practice of medicine. I’ve lost my ability to concentrate or take anything seriously. Having almost daily hangovers doesn’t help, either.

I’m the first one on either side of the family to go to college. My father is the kind of man de Tocqueville must have had in mind in Democracy in America when he wrote about why Americans are more addicted to practical than theoretical science. To my father, college is supposed to teach me a trade.

If I tell him that I no longer think medicine is for me, and that I’m thinking of changing majors from chemistry to English, he’ll tell me to pack my bags and come home. To him, a switch to English would be tantamount to giving the finger to the American work ethic. So I am going to finish my premed distribution requirements. Then I’m going to secretly switch majors and the hell with the consequences.

But. But. Some things about medicine are still so fascinating to me, not the calculus or the organic chemistry, but the hands-on stuff.

I like it when the surgeons are on duty in the ER. They impress the hell out of me: a surgeon is part healer and part mechanic. They can get rough when they have to. They’re not afraid to manhandle. Sometimes they have to pull, shove, and twist parts to get the job done. But other times, they use their hands with a most exquisite precision and finesse.

I’ve gotten pretty chummy with a couple of the doctors at St. John’s, but I particularly like Dr. Kaplan, whom everybody calls Dr. K. He’s a plastic surgeon, and I understand he’s a really good one, from what everyone says. He’s quite round, with a kid’s face and rather stubby hands, at least for a surgeon.

Dr. Kaplan has taught me how to suture. Not on a patient, of course, and not your ordinary sutures. He’s taught me mattress sutures, the kind plastic surgeons use to keep scarring to a minimum. I can’t foresee any situation where I would use this knowledge without ending up in a court of law, but it’s a good party trick back in the dorm. And it’s nice to be able to look at a hemostat and see it for what it actually is, instead of a roach clip.

Dr. K. is on tonight, and I can’t wait to see how he handles what we’ve brought him, out of a deep, dark, rain-soaked night on Queens Boulevard.

We’ve been running all night; there have been accidents all over Queens on account of the pouring rain. It was late, after midnight, and things had finally quieted down, when we got this call.

On the surface, it wasn’t a bad accident. A Beetle had rear-ended a truck at a stoplight, a fairly low-speed collision. The only injured parties were in the Beetle, a young guy and his girlfriend. Both of them were about my age—early twenties. He wasn’t seriously hurt, but she had a nasty head injury: she had smacked the windshield, and most of the flesh on her forehead was missing, just gone, down to the bone.

While we were fixing her up and getting the information we needed, I noticed her boyfriend had booze breath.

Standard procedure on a call is to make a note when we smell alcohol on a patient’s breath—we print a simple AOB on our pink sheet. This isn’t just for car accidents. Pedestrians get loaded and walk in front of cars and trains. People drink alcohol and take barbiturates—and the ER staff needs to know this. We make these notations for all kinds of reasons. But especially when anesthetics may be needed.

Anyone can have alcohol on their breath after only one drink, so merely noting AOB has no definitive legal meaning. Sometimes we simply don’t put it down, like tonight, when we’re busy and it’s raining and we have to get off the road. Also, the boyfriend went RMA—refused medical aid. Technically, he wasn’t our patient at all. So no pink sheet even to write AOB on.

We learned at the scene that these two were well known to the police. He was the son of a sergeant at a local precinct. She was the daughter of a captain at another precinct. All very much a family affair. I’m not sure if they were engaged, but it seemed like they might have been or were close

to it. It’s nice to think of them marrying, uniting two precincts like two kingdoms, a modern-day Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon.

We got her back to St. John’s, and Dr. K. immediately got her prepped in the OR. I say immediately—all these things take a little time, after X-rays, et cetera. The films showed no fractures or internal injuries, so she was ready to work on.

Now I am looking on with Dr. K. as he examines our patient’s head wound. She is flat on her back on the operating table and the depth of the missing skin, combined with the bleeding that won’t stop, is creating a little blood pond on her forehead. Dr. K.’s nurse is sponging up the blood, but as soon as she does, the pond fills back up. Dr. Kaplan appears to be looking for something, but he’s not saying anything. Until he says ha. I have no idea what he’s seeing. Until he shows me.

On the surface of the bloody forehead pond, almost impossible to see, there is a faint ripple in the blood. If you’ve ever taken a hose into a swimming pool, you’ve seen something like this. Just a tiny murmur of fluid. A ripple the size of a pinhead. That’s what Dr. K. shows me. He’s found a bleeder in the pond. But we can’t see the blood vessel it’s coming from.

Dr. K. says he’s going to try to tie off the blood vessel. Not only is it tiny, but invisible under the opaque surface of the blood. This vessel would be hard to see even if it were high and dry. But he’s going to have to do this blind.

He selects what has to be the finest diameter of surgical thread available, as far as I know: 10/0. It doesn’t look much thicker than spider’s silk. I’m watching him watching the ripple. He looks like a bird of prey, an owl, moving his head slightly from side to side, triangulating the source of the ripple—a precise spot that’s invisible to the naked eye. He suddenly takes the plunge, his stubby fingers darting in, and, with a few deft movements, ties that little bleeder off. The ripple disappears immediately, and this time when the nurse sponges, the pond doesn’t fill up again. It’s as impressive as hell.

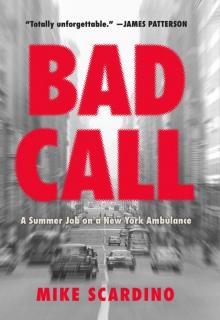

Bad Call

Bad Call