- Home

- Mike Scardino

Bad Call Page 2

Bad Call Read online

Page 2

I guess if you want to see the doughnuts fly, that’s the call that will do it.

This call is behind a private house in Maspeth, right up Fifty-Seventh Avenue, not even as far as the gas tanks. It will only take us a couple of minutes to get there. And here we are. And so are the cops. Three cars.

Come around back, beckons one of the policemen. I’m expecting to see a man down, blood spurting from a gunshot wound. It’s never what you think you’re going to see.

Instead, a very calm man in shorts and a T-shirt is sitting on the grass with his legs splayed apart in an odd way. He’s sitting in front of a charcoal grill. The coals are lit. He’s obviously in distress, but he’s in control. He’s okay enough to tell us what happened. It’s pretty simple if a bit unbelievable.

He was squirting charcoal lighter on the coals, and the can blew up, dousing his legs in burning fluid. That’s it. So this can actually happen. They tell you not to do this on the can. I’ve done it many times.

Not no more.

He really doesn’t look that bad. His legs aren’t even red. But they don’t look right. They look very white, almost like they’re made of alabaster or something. I know what it is. They look like the fat you see on uncooked steak. Thick, opaque white fat. On the side of each leg there’s a thin red line of blood, marking where the epidermis was burned back.

Jim sees me looking and takes me aside so the patient won’t hear. Those are third-degree burns. I am surprised. Not at all what I expected, not having seen third-degree burns yet. What did I expect. Yes, blackened charred flesh. Jim continues, The tissue is dead, there’s no blood. The burns are deep. These are serious burns, he goes on. It’s about the rule of nines. I know about this but haven’t memorized it. Jim gives me the Cliff’s Notes.

When they give a burn victim’s condition as having a certain percentage of burns over his body, it’s totaled up by units of 9 percent. For example, each whole leg is 18 percent. The front of each leg would be 9 percent. Our patient has the front of both legs burned, so he has third-degree burns on 18 percent of his body.

That doesn’t sound like much to me, but Jim is concerned. He gets very quiet when he’s concerned, and the blarney stops cold. Apparently this percentage is very serious when the burns are third degree. Nothing to do but get this poor guy back to St. John’s. Straight shot down Fifty-Seventh and right on Queens Boulevard, and we’re there.

We don’t usually expect any closure on calls. We get so many, there’s no way to keep track. Plus we don’t really want to know most of the time. And, of course, patient information is supposed to be confidential, unless you’re a member of the family. But sometimes we find out anyway.

Word comes down the next day that our policeman patient has died. With third-degree burns that didn’t look like anything, over just 18 percent of his body. It’s so hard to believe. Maybe he died from a heart attack or some other complication. It doesn’t make sense—18 percent is just a number. It just doesn’t seem like that much.

But I guess it was enough.

The Napoleon

I can’t say for sure exactly where we are, except that we’re way up in Astoria. We got this call: woman down. What does that mean. Down. Could mean anything, really.

What is this place. Looks like an old apartment building. Obviously, it was an apartment house, but it’s been converted into some kind of rooming house. The doors to the rooms are all open. The people inside the rooms are elderly, and they look sick. Some are in bed. Some are sitting by their beds, next to walkers.

Nobody seems surprised to see us going down the hall with our stretcher. Most don’t even look up as we go by. It’s not a nursing home in the conventional sense. Not like any I’ve seen. Almost certainly unlicensed. Looks like a homemade nursing home for poor people. A neighborhood co-op nursing home, like a neighborhood garden.

It strikes me that it’s kind of nice that something like this exists. The need was there, and somebody made it happen. The building is clean and the heat is on, even though it’s summer. It is cool outside, but it’s not that cool. Old sick people are always cold. Somebody cares.

I bet it’s a walk-up again. Of course it is. A woman leads us upstairs. She’s not wearing a uniform, but she’s obviously in charge. It’s Sunday. She’s the weekend shift. Probably not an RN or even an LPN. Just keeping an eye on things. I suppose she’s the one who made the call. Good for her. A lot of looking the other way goes on in places like this.

Up we go, three, four floors. There’s a noise, but I can’t place it. We’re going down the hall in the direction of the room where it’s coming from. It sounds like it’s coming from an animal being abused in some way. Jesus. Take a deep breath; in we go.

It’s difficult to describe what we’re seeing; appalling seems barely adequate. There is an obese black woman half out of the bed. She’s making the animal noises. No words. No screams. Just roars and groans and snarly gurgles. Her eyes are wide open, but I don’t think she can see anything. They’re darting back and forth really fast. The whites are the color of yellow mustard, and the pupils are dilated all the way. Her head and upper body are wedged between the bed and one of those huge old ornate radiators they call Napoleons. After the pastry or the emperor, I wonder. Have to remember to look that up. This one was full of steam. These are much hotter than the hot-water kind. Burn-you-to-death-hot.

The parts of her head and upper body wedged against the radiator have turned white. The rest is her natural color. No one knows how long she’s been like this. Didn’t anybody hear the noises. Everyone here is old, so maybe not. She looks pregnant. Pretty sure of that. All her weight seems concentrated in her abdomen. Her limbs look relatively normal in size. She’s young enough to be pregnant. I’d say in her late twenties at most. Why is she here with all these old sick people.

Big Al says she isn’t pregnant. He says she’s in the last stages of cirrhosis, and that’s why her abdomen is so distended. Now we’re guessing she was near the end when she fell and got stuck between the bed and the radiator and was too weak to get free, so she got slowly cooked.

What a break. Dying from cirrhosis plus burned alive by a goddamned radiator.

It’s very hard to get her unstuck, and we have to be careful not to get burned ourselves. The Napoleon is still searingly hot, and no one seems to be able to shut it off.

She isn’t struggling, but she isn’t cooperating, either. She is very heavy, completely inert, and really in there. By the time we get her unstuck and onto the stretcher, she’s not making noises anymore. Her eyes are still darting back and forth.

Does she see me. I don’t think so. I’m talking to her and telling her it’s going to be okay. I tell her we’re taking her to the hospital, and she’s going to be all right—this being one of our more useful lies. I’m thinking what could she possibly understand at this point. And if she can understand me, is it any comfort. Sometimes, I think it is.

I don’t think it matters much this time.

We get her to Elmhurst General, alive, and brief the staff on what we think we’ve brought them. They don’t say anything, but we know they’re dismissive of our cirrhosis diagnosis. That’s okay with me. I know we’re not doctors. We’re just telling them what we were told at the scene. They can see the rest of what’s happened for themselves. They can see it. Who can say if they believe it.

I wonder if she’s going to make it. God forgive me, but I hope she doesn’t.

Mr. Bubble

A Chevy Bel Air has smashed into a tree on a nice street in Forest Hills. The lone driver is the only casualty. He has submarined under the wheel, and he’s stuck in there pretty well. No seat belts in the car. I’m talking to him. He’s conscious but very bloody, obviously in a lot of distress but handling the pain well. He’s being as tough-guy as his situation allows.

He’s a big man. A lot of us say big when we really mean hugely fat. Big, then, is our standard euphemism for obese. So okay, this man is really, really fat. I am thinking

that this fatness probably saved his life when he hit the steering wheel.

It doesn’t look like he had been going very fast, so we’re not expecting extensive internal injuries, but of course it’s impossible to tell just by looking. We’re wondering how to get him out from under the wheel and onto a stretcher. Luckily, at least in terms of his potential extraction, the seat has slammed up toward the front of the car from the impact, and we’re able to release it and slide it back and just ease him out. He insists on walking to the stretcher, which is only a yard or so away. I like this guy.

We get him to St. John’s and into the emergency room. In the ER, we do a cut down, scissoring off his clothes to get him ready for treatment and X-rays.

Most of his face and head wounds are bloody but not serious (head wounds always bleed a lot even when they’re relatively minor). However, he’s having a very hard time breathing now, and he can barely talk. His neck and face are swelling grotesquely. Dr. K. decides something’s blocking his trachea, so he plans to make a hole.

Dr. K. is having trouble. He’s trying to feel for the trachea with his finger—and his finger is barely up to the task, given the volume of neck fat.

Dr. K. is Dr. Kaplan, a plastic surgeon, doing his required periodic rotation in emergency. I’ve always thought his fingers were kind of stubby for a surgeon, but he is really talented. I’ve seen him do some amazing things in the ER and always consider any patient who needs to be sewn up when Dr. K. is on duty to be lucky—relatively speaking.

I think he must take at least eight stitches for every one a regular physician makes. More stitches mean smaller scars. I’ve seen him do mattress sutures so the threads don’t go over the wound and give that traditional Frankenstein’s monster effect. He’s meticulous. I admire him.

Our patient’s neck is looking like it belongs on an alpha-male elephant seal. Dr. K. finds his mark, he opens, and in goes the airway. He is so quick. He secures it with adhesive tape, and we roll our patient into the X-ray room.

When they roll him back to the ER twenty minutes later, we all whisper Holy shit simultaneously. Is this the same guy. I can’t say what his actual percentage increase in size works out to be in numbers, but he’s a whole lot bigger than he was when we brought him in. What is going on.

We all look at his X-rays to find an answer, and there it is. Nearly every single one of his ribs, on both sides, is smashed—splintered in two places—by the steering wheel. The splintered ribs have shredded his lungs, and the air he would normally be exhaling is staying inside his body instead, inflating him like a balloon.

Every part of his body that offers any available space for inflation is blowing up before our eyes. Dr. K. is palpating the patient’s arm. He asks if I want to feel.

What I feel is this: the flesh below the surface of his arm feels like layers of bubbles. The bubbles move around when I squeeze.

Dr. K. tells me what I’m feeling is called crepitus, caused by interstitial emphysema: the spaces in our patient’s body are trapping the air pumped from his lungs into, rather than out of, his body.

We’re standing by to get the okay to take him upstairs to surgery. This can’t wait. It’s hard for me to visualize exactly what kind of operation they’re going to perform. I don’t see how they can repair his lungs, torn to pieces by bone splinters. It occurs to me that they may not know themselves and will just have to see what they can see.

We’re all standing around him. Everybody is staring; it’s impossible to look away. His scrotum is the size of a small grapefruit and his eyelids look like Ping-Pong balls. They’re pressed shut, and he can’t see us any longer. He can’t see us gawking. His neck is gigantic now, and I’m wondering if it could actually expand to the point where it pulls the airway out of his trachea.

I’m starting to think that now I’ve seen everything. But, of course, just by virtue of seeing this, I know for a fact that I have not seen, and definitely never will see, everything.

Through it all, this terrific man is trying to reassure or even comfort us. He’s patting Dr. K.’s arm, as if to say, Don’t worry, it’s going to be okay. We get this a lot. Patients often seem to know when they’re putting us under stress and try to make us feel better. They often apologize to us. This almost always makes us feel worse.

He hasn’t lost consciousness and seems pretty stable. All of which would be amazing in any human being, but he is seventy-eight years old.

We get the call to bring him up, and when we leave him, we pat him on the shoulder and say our good lucks and go away feeling pretty hopeful. Jesus, can this old hoss absorb the abuse. We’re engaged. We’re really pulling for him.

They call down from the OR to let us know his heart stopped before they could even get him on the table. It isn’t surprising.

But after all he went through and survived, it just doesn’t seem fair.

On a Wine-Dark Sea

Someone has gotten me up out of a deep sleep. I’m in the X-ray room on a gurney. It’s freezing in here, but it’s too hot outside to sleep on the stretcher in the back of the bus. I’m aware that my lower face, from the corner of my mouth to below my chin, is covered with dried drool. I am about eighteen hours into a twenty-four-hour shift, 6:00 a.m. Sunday to 6:00 a.m. Monday, so it must be about 12:00 a.m. Monday morning. We’ve been going nonstop until around forty-five minutes ago, when I apparently passed out on the gurney.

We have a call. It’s a possible DOA in Kew Gardens. We don’t go there that much. Fred knows where the address is, though. He knows where everything is. He never seems to need sleep.

I’ve known Fred since before I started on the job, when I used to pump gas at my father’s gas station for the St. John’s ambulances and hobnob with the ambulance boys, as Dad called them. Although Fred hardly qualifies as a boy. He seems very old. Not so much in years but in mileage. He’s from the Deep South. Way deep. He has a heavy accent. Maybe Mississippi or Alabama. No farther north than that.

Fred is one of those to-the-bone southern guys who grew up with absolutely nothing and will never let himself or the world forget it. But I’d never call him a redneck or a cracker. He’s smart as a whip. Skinny as a snake. Mean as a mink. His eyes and cheeks are sunken in, and his nose is huge and hooked. He looks like a large raptor, in profile. Maybe a turkey vulture. Check that. He actually looks like a dead man.

Fred is dead serious about everything and pretty much a drag to be partnered with, but he knows a lot and I feel confident when we’re out on a call together. The only time he smiles is when something is bitterly ironic or when he tries to be social and make a joke, which he can’t. Maybe he realizes he can’t make a joke, and the smile is more of a rueful grimace. He’s surprisingly strong, like a lot of these wiry, leathery old southern guys are. My Nashville grandfather was the same way—tough and wiry—but as gentle a man as you’d ever want to meet.

I outweigh Fred by at least fifty pounds, but I wouldn’t want to fight him. His snake is out and his 11s are up, which isn’t good. The snake is what the winos call the blood vessel that becomes prominent on the forehead of someone who’s in bad shape; the 11s are the tendons at the back of the neck that, when wasting is at work, stick out like the number 11. The 11s are considered much worse than the snake, as these things go. My guess—he’s in his late fifties but could be younger. Life has not been kind to Fred, but he’ll probably live to be a hundred. These hard, skinny guys are usually the ones who do. Except for the nice ones, like my grandfather.

He’s been divorced a long time and lives alone. He doesn’t smoke or drink. I’m not sure I’ve ever seen him eat, which is virtually a team sport with our ambulance gang. I’ve never been aware of him taking a break for either number one or number two. What he does with his waste is anybody’s guess. Is it possible, considering his meager consumption of food and drink, that he actually produces no waste.

So Fred is awake and not talking, and I’m half asleep and incapable of talking, and off we go. No conversation. No li

ghts or sirens, either. There are cops on the scene, and it’s not a rush call. They must’ve woken me up out of a dream on the gurney because it seems like the dream is still in progress.

Here’s the house. The patrol car is out front. We go inside.

It’s very dark in the house. It seems a lot darker than it should be, even at this wee hour. Here’s a little old lady. Who’s dead and where are they, I’m wondering and before I can finish the thought, she tells me it’s her husband and he’s in there.

There is a tiny bathroom, barely big enough for the toilet, sink, and tub, which are arranged left to right as I’m looking into the room. What I am seeing is strange and striking. I have to attribute this in part to my extreme fatigue and the fact that many times, very late at night, calls take on a decidedly surreal character that is mesmerizing. But this only looks surreal. It is quite real.

In the middle of this white chamber, on the floor in front of the sink, lies a man curled up in the fetal position. His skin is as white as the porcelain tiles, the sink, and the tub. His pajamas are white. His hair is white. He is lying in an evenly spread aspic of congealed blood. The blood is a gorgeous deep purple red-black. It has a smooth, glossy finish like some sort of fruit glaze on a pastry. There is a four-inch-long clot of dark blood coming out of his nose. This is the entire scene. All white against deep red-black. It’s stunning. It’s Homer’s wine-dark sea in forty square feet.

I’m having one of those visual experiences I think they call a trombone shot in the movies. I feel like I’m zooming out and hovering about seven or eight feet above what I’m seeing. This seems to happen a lot on the job, and I can’t account for it.

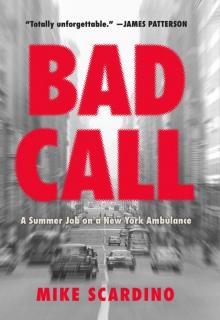

Bad Call

Bad Call