- Home

- Mike Scardino

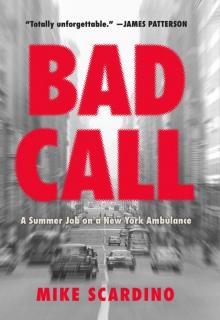

Bad Call Page 3

Bad Call Read online

Page 3

What I also can’t account for is why this scene strikes me as beautiful. Of course, it’s not beautiful in any conventional sense. It’s horrible. A man is dead. He bled out on his bathroom floor. Most likely too much blood thinner plus a major nosebleed.

I’m trying to think what beautiful really means. I think most of the time, for most people, it means something good. But I don’t think it has to mean good. I’ve heard the phrase a terrible beauty, and I’m thinking, Yes, this is that. It is terrible. And it is beautiful.

And it’s unforgettable.

Beer

There’s a full moon, and Fred and I have been ready for some serious action all night, but it’s about 3:00 a.m. and we haven’t had any so far. There are supposedly all kinds of statistics about the full moon’s effects on humans: more murders, more crime in general, lots of maternities, and so on. But ole Fred don’t need no stinking statistics: he knows this is true from firsthand experience.

Yes, it’s uncannily quiet out there tonight. Crap. I would have to say that—now we’re getting a call saying there’s a bleeding psycho in the basement of an apartment building in Rego Park. What a wonderful, melodramatic term, psycho. I wonder which came first—the street slang or the movie. The word itself tells us next to nothing. Other than it’s not a DOA or maternity or man off a building, and we should be cautious since we have no idea what we’re walking into. It could even be dangerous. I’m getting all shivery: a full moon and a psycho. Lon Chaney Jr., here we come.

It’s a nice building. The call is in the basement, which is apparently an apartment rather than simply a utility area, where the furnace and the laundry equipment are usually located. The door is cracked, and the cops push it open. It’s hard, because something is pushing back. Inside is a sea of empty beer cans. Hundreds and hundreds. Maybe thousands. They’re at least a foot deep on the floor and rise gradually as they meet the walls, going up at least three feet in places. I think I see the outlines of some furniture under the cans. It looks like a Georgia farm where everything is covered in kudzu.

The smell of sour beer and piss and vomit is overpowering. It’s stifling hot in here. There’s no damn air. We can’t open any windows because we can’t get to them for the beer cans.

In the middle of the room, sitting back on a huge mound of empty cans, is a man about fifty years old. He has on a uniform that’s covered in puke and blood. One of the cops says he’s a beer-truck driver. Oh God, the irony. I allow myself to think this is funny, just for a moment. The beer-truck driver as the little kid with the drink stand who ends up consuming a lot of his inventory himself. I wonder how long this has been going on and if his employer has gotten feedback from customers about their orders being less than complete.

The man’s name is Bill. Fred and I chassé our way up to Bill, our feet flat on the floor under the empty cans, sliding smoothly through them to take up positions on either side of him. Hi, Bill. How are you feeling. Do you want to go to the hospital. Do you think you can stand up. He nods yes and yes and tries to say something but can only make gurgling sounds. His mouth is full of blood; it’s coming out the sides when he tries to talk. He’s bleeding a lot. Bleeding ulcers perhaps. That’s my bet, given the huge quantities of beer he must consume on a regular basis.

His pulse is still okay, and he’s alert and looking at us when we speak to him, but that won’t be the case for long with this much bleeding, so we have to get moving. Anyway, judging by his alertness, Bill is no psycho.

Whoever made the call probably hadn’t seen him for a while. Maybe he didn’t show up for work, and his boss called the landlord, and the landlord knocked and only heard gurgling and thought Bill was going nuts. The call probably came in like: I have this tenant and can’t get in his unit and he’s making these animal kind of noises and I’m afraid he’s crazy or something…Direct translation from Central to St. John’s 433: Psycho.

Bill, can you stand up for us. That’s good. Do you think you can walk with us to the ambulance outside. Great. It’s not that we’re lazy. This is just more efficient. We could go back through the cans, down the sidewalk, open the doors, and pull out the stretcher, then make our way back, but it’s a time waster, and Bill is nodding and gurgling, Yes, I can make it, so off we go.

All the way I’m asking him what happened, and it seems like he’s really trying to tell me, but I can’t understand a word of it, and neither can Fred.

We help him up into the ambulance, but he clearly doesn’t want to lie back and would rather sit up on the stretcher, which is reasonable, given that he would almost surely choke on his own blood if he were to lie down. I look under the bench seat and bring out a handful of plastic bags, because he’s bleeding that bad.

We love these plastic bags. When patients vomit or bleed orally, these bags are a must. We buy them ourselves because the equipment they give us for this, the intolerably cutely named emesis basins, is absurd. These stainless-steel basins are the kidney-shaped bowls you see when your doctor gives you a shot and needs a little container to put the gauze and syringe in or whatever. They’re really small and hard to grip and, worst of all, they catch and hold almost nothing. Ambulance-worthy patients who vomit almost always do so in large volumes, and to see it come blasting out in a moving ambulance and hit the rounded sides of the dainty basin and carom off onto the stretcher and the floor of the bus and your uniform and arms and face is not any fun at all. The plastic bags hold a lot, and you can tie them off.

Bill, see if you can hold this for me. He can. The bag is filling up as I get out my pen and pink sheet on its little clipboard and try to get some information. We’re moving fast. Full lights and siren. I have learned to write pretty well in a bouncing, lurching ambulance. The downside is I seem to be losing the ability to write legibly when I’m sitting still. Fred radios Central and tells them we’re 10-20 to Elmhurst General with a rush bleeder and they should be ready for us. Amazing. From psycho to rush bleeder in the blink of an eye. You just never know.

Bill still can’t talk. His bag is half full, and I hand him another. He’s trying to tell me something, over and over again. It has a speechlike cadence to it and almost makes sense. It sounds like Ah ankh ayno. Sounds vaguely Egyptian. It must be the ankh part. He’s clearly frustrated that he can’t get it across. For sure no psycho. Not even drunk, although I don’t see how that’s possible, given all the empty beer cans.

Bag number 2 is ready to tie off, and I place it carefully next to the first and hand him a third. We’re at an impasse. He’s still trying to tell me what’s wrong. I still can’t understand him. He’s still bleeding. I wonder how many bags he can go through before they’re all full and he’s empty.

I think we may have a breakthrough. There is an aha light in Bill’s eyes, and he starts pointing at me. It scares me for an instant. It feels like some kind of accusation or warning. Oh. He’s not pointing at me; he’s pointing at my pen and the pink call slip on my clipboard. He trades me his bag for my pen and paper, and he immediately writes: I drank Drano. Oh shit.

Shit, shit, shit.

I look at his words, and then I look at him, and just to make sure I’m reading this right, I shout (Fred is standing on the siren and it’s deafening), You drank Drano, and Bill nods very slowly. He looks like a kid who has just confessed to breaking a prized knickknack. He’s ashamed.

I hand him back his bag, and he continues his bleeding. I put my pen in my pocket to concentrate on doing whatever I can for the man, which is pretty much nothing. He can’t lie down, so all I can do is steady him as we jounce along and have more bags ready. All the while I’m wondering how this happened.

Was he in a stupor with an upset stomach and thought he was taking Bromo-Seltzer or something like that. Was he trying to kill himself. He could have picked a better way. When I say better, I don’t mean more effective, just quicker or less painful. I know that most would-be suicides who survive a jump tell of regretting it on the trip down. If suicide was Bill’s plan, I imag

ine he’s regretting it now.

I am thinking about what is happening inside of Bill. Drano is a strong base and just as caustic as a strong acid. It is burning through Bill’s flesh and disintegrating his capillaries as it makes its way through his digestive tract. The capillaries in his mouth and throat, his esophagus and stomach. This kind of bleeding isn’t like arterial bleeding, where you can apply pressure and stop it or at least slow it down until it can be tied off. What’s to press. This is why wounds to the stomach or liver are so tricky. They’re full of capillaries and it’s so hard to stop the bleeding. I think most people picture bleeding to death as blood spurting dramatically out of an artery. Bleeding out. But oozing out is just as effective, if less flamboyant. Then there are the chemical burns to the other tissues. I’m trying to picture how much of Bill’s esophagus is left when we pull into EGH. Poor Bill.

There are a lot of personnel, an unusually high number, in the ER when we roll in. Must be the full-moon contingent.

We get Bill into a wheelchair and roll him in, bag in hand. We step back quickly because Bill is immediately swarmed by a cordon of residents, interns, and doctors of every stripe. Word that we were on the way with a Drano case seems to have drawn every available MD from whatever he or she was doing to see it. What they are going to do for Bill is anybody’s guess. My guess is: nothing.

Tonight I had plans to go out with my friend Gary and have a few beers. I think I’m going to pass.

Breakfast of Champions

Central says we have a female DIB (difficulty in breathing) and put a rush on it. We’re off. No need for the lights or siren. There’s almost nobody on the road. It’s about 5:00 a.m., and most New Yorkers sleep late on Sunday. We’ve been on since 6:00 a.m. yesterday, almost finished with a twenty-four-hour shift.

I’m on with Andy Panda (he hates that nickname, and I never use it to his face, obviously), and we’ve had a hearty breakfast—egg sandwiches, the wonderful kind with the yolk that spurts out when you bite down, and hash browns and doughnuts and Danish and two coffees and juice. We bought a New York Times to share. One of us will take over the puzzle when the other one gets stuck. In the unlikely event that one of us finishes the whole puzzle, we’ll buy another Times.

Andy’s one of my favorites. He’s a big guy, like a big teddy—or panda—bear. Baby faced. Like a big kid. He lives with his mum—he really calls her that. They emigrated from England when he was just a nipper. No mention of his father, and I’ve never asked. One time we stopped by their apartment, and I met his mother and he showed me their prized possession: an ornate helmet they claimed came from the Light Brigade. I didn’t see any cannon-shrapnel holes. It looked really new and was well polished—like something the kaiser would have worn to inspect his troops. I was skeptical, I have to admit. But I did my best to appear appropriately appreciative.

Andy never went to college, but he’s exceptionally well read. Plus, he’s naturally smart, which helps him take his reading and turn it into understanding. That, combined with the street smarts you get on a job like this, makes for a very tolerable twenty-four-hour-shift companion. He definitely knows his shit as far as emergencies are concerned. He’s not that much older than I am, at nineteen, but he seems older and wiser, and I tend to think of him as kind of a big brother.

Andy works two jobs. Several of the St. John’s guys do. This is one reason the night shift is so popular—it gives them time for another gig. Some of them make pretty big bucks for blue-collar guys—but that’s always been true of NYC: if you want to bust your hump, you can make some serious cash. I can make tuition for a year at Vanderbilt working for St. John’s in a single summer. It’s good money. But I’d never have the energy to take another job in addition to this one. I don’t know when those guys sleep, but they seem healthy and alert enough. Mazel tov, boys. Better you than me.

Andy’s other job is driving the truck that collects corpses from the city morgues and delivers them to the potter’s field on Hart Island. This is one of those jobs you wouldn’t dream existed unless somebody told you about it. And if you did know about it, you’d never figure out what you had to do to get it. There’s a whole parallel reality of jobs like this in a city like New York. Hidden jobs. Jobs that almost no one is aware of as they go about their day-to-days.

Dad has a guy named Steve who opens up the gas station every morning at six. When I was little, Dad told me the reason Steve got there so early was because he was coming from his other job, which was turning off all the streetlights in the city. This fascinated me until I realized that, like Santa visiting every rooftop in the world, it was absurd. But when I think of Andy’s morgue job and others like it, I think of Steve and the streetlights and wonder how many other strange and secret New York jobs that might seem absurd are, in fact, real.

Andy’s morgue job is dead simple. Pick up the van—it looks like a bread truck—and then make the rounds. I’ve seen these trucks from the outside. They’re custom fitted, with multiple coffin racks installed for the unclaimed dead. That’s who goes to the potter’s field—the unclaimed. Some of them have not been identified. Some have been identified, but there’s no one to notify, to claim them for burial. Some of them belong to people who have been notified but have no money for a burial. And some of them belong to people who have been notified but couldn’t care less.

New arrivals are buried three deep and carefully cataloged for possible reburial if someone should eventually show up to claim them. If not, Andy tells me, they wait six years, and if no one has shown up, they exhume what’s left and dump the remains out at sea. I have no way of verifying this. I guess I will have to file this with the helmet from the Light Brigade: Hold for verification.

He says he has seen some pretty awful things on his morgue job. The one that sticks in my mind is his description of a morgue attendant jumping up and down on a body to get it into one of the pine boxes they use as coffins. This I can believe. These boxes are impossibly narrow. I’ve seen them and I can’t see how anybody fits. So I could understand how they might have to use a bit of force to get a body into one, since it’s definitely not a one-size-fits-all proposition. Rigor mortis is not a consideration—it’s usually gone in a couple of days, and the unclaimed bodies are in the morgue at least that long before they’re boxed up. They are embalmed before burial, but they’re kept at only around thirty-four degrees Fahrenheit before that. I suppose if they froze them it would damage tissues and prevent an accurate autopsy.

The fact that they’re not frozen means they make the whole place stink. When I see a movie or television show where a jolly ME is sitting in the morgue munching on a sandwich, it’s really irritating. It would make me want to throw up.

I had a hair-trigger gag reflex growing up. I got carsick almost every time I got in a car. I couldn’t eat pasta with tomato sauce for several years, to the great amusement of my father’s side of the family. The Italians. Even colors, one in particular, set my gorge to rising: a pastel aqua-green. A color found on certain Fords of the day as well as some flavors of saltwater taffy. Considering the truly awful smells we encounter on the ambulance—decomposition, gangrene, gastrointestinal bleeding—I’m amazed I’ve never hurled. Visual stuff like carnage, blood, gore, and the like have little effect on me, at least hurl-wise.

Here we are. Let’s meet our rush female DIB. Well, bless her heart—it’s a sweet little old lady. She’s conscious, and her color is good. Her pulse is okay. I don’t think she weighs more than seventy pounds. She’s communicative. Hello, Mother. (I’ve picked this greeting up from the other guys when we have a call with a patient like this. They seem to love it.) She’s having moderate difficulty breathing but nothing that seems immediately life threatening. We lift her onto the stretcher—she’s as light as a marshmallow—and roll her outside and into the ambulance.

We’re under way. Now she seems to be having more trouble. I raise the back of the stretcher a bit higher and start giving her oxygen. The mask is over her mouth and no

se. Are you comfortable. Is that too tight, I ask as we bounce up Queens Boulevard. She wants to tell me something. She’s insistent.

I take the mask down and lean in close to ask her what she has to say. I am in midsentence when she vomits directly into my open mouth.

I, in turn, immediately encase her in generous amounts of egesta composed almost completely of the huge breakfast I have consumed not twenty-five minutes prior to this very moment. Some of the ingredients are still quite recognizable. She, however, is not.

Her entire head and shoulders are obscured with the remains of my morning meal. I’m horrified. Mortified. As I stare at her unrecognizable form, I can see movement. Two apertures open up in the mass that is covering her face, and I see her shiny blue eyes looking at me through the vomit. She is blinking slowly. Her mouth is open, but she isn’t saying anything. Interestingly, she no longer seems to be having any difficulty breathing. Have I shocked her into wellness.

I look up and see Andy’s eyes in the rearview mirror. Total shock is an understatement.

We’re pulling into St. John’s. I see the looks on the faces of the staff as we roll our patient into the ER and transfer her to a gurney. They don’t have to ask what happened. They can see that. Maybe later, they’ll ask how. Right now, they’re as stupefied as our patient, Andy, and I.

So much for my perfect no-hurl record as an attendant on St. John’s Queens ambulance. I suppose, like any record, it was meant to be broken. In rather extravagant fashion, at that. Andy says I’d better change my shirt and rinse my mouth out while I’m at it. I told you he was smart.

Boudicca Goes Soft

It’s a nice, quiet Sunday morning, and I’m at my command center in the ER. It’s a desk with a phone behind a high counter, where I can sit to take calls and relax when we’re between runs. There’s another room to the side of this where some of the other guys regularly congregate to read the paper, eat, or just bullshit. Usually we’re all outside, and someone who’s covering the phone will come out with the call. But when it’s hot or when we’re noshing, we like to be inside with the AC.

Bad Call

Bad Call