- Home

- Mike Scardino

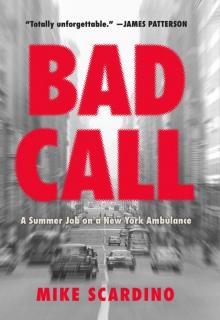

Bad Call Page 7

Bad Call Read online

Page 7

Sorry, Sten, you can’t smoke in the ambulance because of the oxygen. Sten says nothing. Then he says just one word.

Please.

It’s hot out, even at this hour, and all the windows are open. There is no air conditioning on this bus. Andy is driving slowly. I’ve never seen him drive so slowly. I’d say we’re going no more than fifteen miles per hour. Even creeping along at this speed, we feel the bumps clearly. Every street in the city is made of bumps, having been paved, dug up, and repaved more times than anyone can count. The suspension on this vehicle is just a degree or two more advanced than that of a Radio Flyer wagon. One bump = one outcry. Sten is going through hell. We’ve got nothing for him. The least we can do is let him smoke.

Once again, I’m thankful I’m not the senior man. I don’t have to decide whether we’re going to break another unbreakable rule tonight.

Andy slows down even further, almost to a stop, and turns to speak to me. I guess he heard Sten say the magic word.

Give him a butt, Mike. And give me one, while you’re at it.

Silence Is Golden

It is so dark out this morning. It should be lighter—the solstice was only a couple of weeks ago. I’m just about dead right now; we’ve been going crazy with calls all night, and none of us, on either ambulance, has gotten any sleep at all. The Zombies of Queens Boulevard. That’s us. It’s a little after four. Not too much longer now. Even though our shift nominally ends at 6:00 a.m., we all try to relieve one another no later than 5:30. It’s silly, but it does create some kind of artificial carrot to keep us going a little longer. It’s just a game, but we are simple working folk, and we live by games like this.

Call. Possible DOA in Forest Hills. I’m on with Enrico. I can’t say I’ve ever heard him say more than a few syllables at a time, and that only when sorely pressed. He’s short and dark and I think he’s from Naples. For all I know he has an accent, but I haven’t heard enough actual speech come out of him to tell. He looks like the love child of Perry Como and some mythic entity, maybe a gnome. He has that gnarly gnome face and Perry’s perfectly sculpted, razor-cut hair. In a certain light, this combination of incongruous elements can be strangely fascinating.

Enrico smokes guinea stinkers all day long. Either smokes them or has one stuck like a permanent fixture in the corner of his mouth, like Big Al. These things do look kind of cool, but they’re nasty, made from the worst possible tobacco you could imagine. One morning things were slow and we were all outside in the yard talking trash when Enrico asked me if I wanted to try one. He didn’t actually ask in words. He merely held the open pack toward me with one cigar extended for me to take. He stared at me, waiting for me to respond. Sure, why not.

I had been smoking for a while, mostly pipes at school (but tons of cigarettes since working on the ambulance). Some of the tobacco is pretty strong, particularly a brand in a can that comes from Scotland, called Four Square Curlies. Several times I got too dizzy smoking this mixture to study—reason 15 in my I’ll Study Later catalog. The dizziness would pass after an hour or so, and I would then move on to an alternative reason not to study.

A lot of first-time smokers get horribly sick from their initial exposure to nicotine—which is not surprising, given that it’s one of the deadlier poisons out there. I prided myself on the fact that I never had. So when Enrico offered me a Palumbo to smoke there in the ambulance yard, I lit up without a second’s hesitation. All three of my coworkers watched me intently. I made the international sign for no big deal—the downturned mouth, with raised eyebrows and shrugged shoulders. Enrico spoke, which startled us all a little: Wynchounhale. Huh. Oh. Why don’t I inhale. Okay, fine, if it will make you happy. I took three or four deep drags. That was all it took. Everyone looked at me with grins of evil anticipation. It didn’t take long for them to get what they were waiting for.

I spent most of the day, when I could, lying on the stretcher in the back of 434. It was a horrible kind of sick. Nauseated and dizzy; mostly dizzy. It wasn’t like a hangover. I didn’t feel that throwing up would do any good. I actually wanted to throw up, but it wouldn’t come. I wondered if anybody who smoked these things ever did inhale them or just sucked on them, unlit, as some sort of big-boy Binky. This episode closed the book on my Palumbo Period.

Today I’m virtually comatose from lack of sleep. We’re on the way, Enrico and I, to the DOA in Forest Hills. I like going to Forest Hills. It’s a nice neighborhood for the most part, and you don’t see the kind of depressing living conditions you see in other areas. There’s the projects, which you’d expect to be rough, given the poverty. What you don’t expect is the squalor you sometimes find in supposedly solid blue-collar neighborhoods. I can take a lot. Blood, gore, the entire catalog of horrifying things that can happen to a human body. What often bothers me more than seeing how people die is seeing how they live.

Caruso stops the bus without a word. In we go.

It is very dark in the apartment. One light is on, in the kitchen. Outside, morning twilight is just getting started. The best way to describe the light outside and inside is murky. There seem to be an awful lot of people here for this hour of the morning. There’s a woman about forty. There are two uniforms. And there are two guys in suits. I simply cannot integrate all of this information, and I’m too tired to ask. Let them just tell me what’s going on, for once. Lead on. One of the cops points me toward a door, which turns out to be a bedroom. I can tell he’s not coming with, and neither is Enrico. Okay, let’s get this over with. Inside, there are two more men in suits. Are they from a funeral home or something.

There’s a dead man in the bed. Very clearly dead. He’s backlit by the murky light coming in through a window. Indigo-blue light. I can barely see. Why doesn’t somebody turn on a light for Pete’s sake. The woman has come in, and she’s standing by my shoulder. I guess she’s waiting for me to say something or ask some questions, questions someone like me would ask in a situation like this.

I’m about to launch into our usual patter. This patter consists of small talk we make to keep the next of kin from going primal on us. It’s designed to distract them momentarily, like when you shine a bright light in the eyes of a frog that you want to gig, if you’re into that. Needless to say, Caruso doesn’t do patter.

The patter usually goes something like this: Bless his heart, was he suffering from any condition, did he have it long, was he being seen by a doctor, et cetera. Very clinical and pretty much irrelevant. Yet it usually lulls loved ones long enough for us to get the information we need and get out of there before the shit hits the fan.

I’ve been staring at this body and seeing nothing but a corpse as the woman stands patiently and silently beside me. She is almost surely the spouse, but I never assume anything. Before I turn to patter her up, as my eyes are becoming adjusted to the dark—or maybe it’s getting lighter outside, probably both—I see something I hadn’t seen when I first came in. I come wide awake. Fast. There is dark material on the pillow under and around the back of the man’s head. Ah. Blood and brains.

I shift my eyes down the bed, without moving my head. I don’t want it to seem too obvious that I’m scrutinizing the scene carefully for the first time. Peeking out from under the blanket and sheet, barely visible, is the tip of a rifle barrel.

On the window-lit side of the man’s head, just under his jaw, there’s a perfectly round, dark red hole. Mystery solved. The suits are detectives, of course. Our DOA either shot himself—or not—which is why they’re here. At any rate, he was shot and he’s dead and we’re done. What an ass I almost made of myself. I came that close to pattering up his wife as to what she thought the cause of death was.

I’ve decided as of this call that Caruso may be onto something.

Those Guys

Who doesn’t love a good gangster story. Those hard-bitten, good/bad-but-not-evil guys we all love to hate. Slaughtering one another wholesale. Standing up to the law: giving a big fat middle finger to the cops, the c

ourts, the finks, the wardens, and the screws. You dirty rats. Come and get me, coppers.

Bad guys are a fact of life in Queens. We all know a few people we are reasonably sure are connected. I grew up with friends whose dads are probably in. I don’t ask, and they don’t have to lie about it. They live their lives and so do I and we all get along fine.

Some people think those guys only hurt their own. But anyone who has ever run a bar or restaurant or done commercial construction knows better. Sure, it’s rare for an ordinary civilian to get seriously hurt or killed as long as they do as they’re expected. But if you’re in business with the bad guys, whether it’s drugs or loan-sharking or prostitution or even running a pizza place or uniform service, you know what your life is worth if you do something to piss them off.

When they do get pissed off, they leave their calling cards at random all over town. My father had a car parked for several days near the gas station, nearly blocking the driveway. It reeked. The cops finally came, and there was a decomposing body in the trunk. I guess they didn’t have time to run the car over to La Guardia or Kennedy.

Big Al and I once had a call in a vacant lot. A man bound hand and foot and beaten to death while sitting in a chair. Might have been shot, as well, but he was too messed up for us to see any bullet holes. And the holes those guys leave are really small; they do love their .22s. Quiet, unobtrusive, and oh so effective, especially up close. No sloppy exit wounds, either.

As I say, it’s rare that they hurt a civilian for no apparent reason. Rare, but not unheard of. The guy I’m looking at now is proof of that. We may even find out what happened, if he can stop sobbing and babbling incoherently long enough to get his story out.

We’re up on a hill overlooking Manhattan, on a road roughly parallel to the Long Island Expressway, looking west, just before the Midtown Tunnel. You’ve probably seen it many times in still photos and movies. On the right, there’s a big redbrick church. We’re surrounded by Calvary Cemetery, which covers well over three hundred acres. At least a few of my relatives are buried here. Along with millions of others.

We got this call as a man down.

I would say he’s about as down as a man can get before being all the way down. Like down-in-the-ground down.

He is a bloody mess. Looks like he has several fractured bones, including a few fingers, one radius-ulna combo, a wrist, maybe his jaw, and very likely a good-sized fracture or two in his skull. His nose is crushed, and the orbit of one eye appears to be seriously deformed, even though right now it’s hard to tell how seriously, because of the swelling. Looks like some of his teeth have been knocked out. His mouth is full of blood, so it’s hard to tell if the missing teeth are old missing teeth or newly missing. He has pissed himself copiously, although some of the dark staining in his crotch could be blood. He is as terrified as anyone we’ve ever picked up. I’m trying to think if I’ve ever seen anyone beaten this badly who was still alive. I don’t think I have.

I do know that I’ve seen people beaten not nearly this badly who were dead.

One thing is clear just by looking at him. Whoever did this knew what they were doing. He was beaten very carefully, with maximum attention to efficiency and detail. With just enough force to maim him as much as possible and yet not enough to kill. There were well-honed skills involved here. It’s actually kind of impressive, in a sick way.

I’m wondering if he’ll be able to settle down enough to tell us the story, but I don’t think so. We can’t wait—he needs to get treatment, stat. Doesn’t matter. The cops know what happened because someone came forward and told them: someone naïve enough not to know enough to keep his mouth shut.

He’ll probably realize what he did just before he goes to sleep tonight and break out in a cold sweat. I mean just before he tries to go to sleep.

Apparently there was a big funeral procession heading to a burial at Calvary. Because it was so big, the cars carrying the attendees were really spread out. As is sometimes the case even with ordinary funerals, red lights are more or less ignored. The cops say our victim was driving west in a path that took him directly across the southerly direction of the procession. He had a green light. The spacing between the cars in the cortege had gotten so wide that our victim must not have even been aware he was cutting off a funeral.

But this was not an ordinary funeral.

As soon as our patient had crossed the street, a black sedan pulled out of the procession and followed him, proceeding to overtake him and pull in front of his car, forcing him to screech to a halt. Then out popped four men, up popped the trunk, and out popped the baseball bats and ax handles. The rest, as they say, is history.

So much for the bad guys not picking on innocents. The bad guys do what they want to do, when they want to do it.

That’s what makes them the bad guys.

A House Like Mine

When I was in the Boy Scouts studying knots, we used to make hangman’s nooses. We were told they had to have exactly thirteen turns. I always thought that was so melodramatic. Or, at least, redundant. As if you had to include a symbol for bad luck just to underline the fact that this knot was going to be used to kill someone.

I could never get my hangman’s noose to work right. I mean theoretically, of course. The ropes we used for knot practice were too soft, like clothesline, and I believe you need stiff rope for a good hangman’s noose, so the free end will slide easily through the loops. A brand-new sisal rope, the kind that’s all bristly with fibers, would be best. I wonder if the pros reuse them. If so, they would have to be adjustable. Maybe they have laws against reuse. They used to hang people in New York but switched to the electric chair and last used that in 1963. There are still professional hangmen in the United States and elsewhere, though. And I thought my job was bad.

They say it’s quick—it’s supposed to break your neck. That’s what the hangman’s noose is for. It’s constructed to abruptly snap the head to the side, to sever the spinal column. But that’s an official hanging, an execution, with a gallows and a trapdoor and the whole nine yards.

But there are a lot more unofficial hangings, where a hangman’s noose isn’t employed—suicides, homicides, lynchings. Hangings where it’s doubtful the deceased had the dubious luxury of getting a nice clean broken neck instead of being slowly strangled by his or her own weight.

I’m on with Fred, and we’ve got a possible DOA in Woodside. Man hung. We don’t usually get that much information, so we have a general idea what to expect this time. Actually, I’m sure Fred has a general idea, or even a very specific idea, since he’s been to hangings before, and I haven’t.

The only mental images I can come up with are from the photographs of hanged persons I’ve seen in books. And from descriptions in literature and the bull people shoot when they don’t know what they’re talking about. For one: they say the eyes and tongue bulge out. I haven’t seen that in the photographs. I guess it’s possible.

If it works right, there should be no bulging eyes or extended tongue. It should be no different than any ordinary, everyday, lethal broken neck. And that I have seen. It’s intended to be quick, but I don’t think it’s instantaneous. Very few deaths are. And of course there are the Ripley’s Believe It or Not!–type cases, when it hasn’t worked and the intended victim has gone free, or so the stories go. Interestingly, I’ve never read one about someone who lived and ended up quadriplegic. I guess there’s nothing Ripley-esque about that—doesn’t make for a very good story.

There are two police cars here, and one of them is unmarked, so my first guess is they think this hanging may be—make that is—suspicious. He’s down in the cellar, you guys, says the officer who’s been waiting for us. Follow me. We do.

This is a pretty nice house, not much different from our house in Bayside. In fact, it’s almost identical—one of the houses Sears used to sell out of a catalog. Apparently it had all kinds of models, from modest ones like this to Tara look-alikes.

This one is f

rom the midteens. The Hillrose style. For about fifteen hundred dollars, you got the whole kit delivered to your site. Assuming the site was prepared, all you needed to do was put it together or find someone who could. Like a big scale model but with stuff like plumbing and wiring on the inside and no decals to mess up. How well it went depended on the model builder’s skill in putting everything together. This Sears house is a good one. Better built than ours, I think.

How do I know all this. My parents’ neighbors found an old Sears house catalog and gave it to them one Christmas. That’s how.

The fact that this place is laid out like my own house is giving me a slight case of the creeps. We’re going down into the basement, and it’s as if my mother has sent me down to get some potatoes or something. Except that none of my family members are here. In fact, other than us and the cops, there is no one at home apart from the gentleman in the basement, hanging quietly from one of the joists, wearing blue boxers, a white T-shirt, and no shoes.

If I had a buck for every dead man we’ve found wearing almost exactly the same outfit, I’d be able to treat the entire ER to pizza. Blue boxers and a white T-shirt. Or white sleeveless undershirt. It has to be a really unlucky wardrobe option. Or maybe it’s not an option. Maybe it’s more of an omen. Like a dead man’s hand in poker.

There are a couple of bare light bulbs hanging in the basement and lots of shelves, tools, and cubbies, all exceptionally neat and orderly.

In fact, neat and orderly is how I would have to describe this entire scene. That is one major way in which this house differs from my own. Not that we’re slobs. But there are six of us. I don’t think anyone else lives here except for this man. Lived here.

The deceased is a forty-four-year-old Hispanic male, according to the ID the detectives have found upstairs in the wallet in his pants. Neatly folded, I bet.

Bad Call

Bad Call