- Home

- Mike Scardino

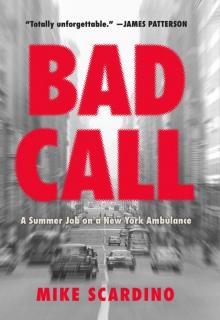

Bad Call Page 18

Bad Call Read online

Page 18

The problem isn’t coming up with a suspect; it’s coming up with enough evidence to get a conviction, which is not always so easy. Of course, there are exceptions, but in general crime solving is nowhere near as complicated as Conan Doyle made it seem for Sherlock Holmes.

Everyone in the crowd, which has now grown to at least twenty-five souls, agrees: the perpetrator is a twenty-seven-year-old guy from Ecuador. Hedunit. Well, that makes things pretty simple. Anybody happen to know this guy’s name or where he lives, says one of the officers, getting a little greedy. No, says the neighborhood Greek chorus. But he always hangs out around such and such street and likes to frequent the same gin mill as his deceased date. Oh yes, and they have seen her with him on several occasions. Plenty of times. Wow. They know exactly who it is, if not his name, his age, where he’s from, and where he hangs out.

Good for you, the Prying Eyes of Queens. Put out an APB on the guy from Ecuador.

Anyway, now everyone knows just about everything they need to know, with only a few loose ends to the story. The theory is our victim went out as usual, met up with Mr. Ecuador, whom she apparently already knew, came home, and something happened to cause things to get out of hand. What could that have been.

When I was nine or ten, in Bayside, there was a notorious murder a couple of blocks from our house. A woman had been walked to her door by her boyfriend, after a date, only to be confronted there by her husband. The woman wound up dead. You’d expect the husband to be the killer, but it was the boyfriend. The word was that he didn’t know she was married and was infuriated by the appearance of her spouse. He stabbed her on the spot, leaving the husband alive as an eyewitness. In France, they might have called this a crime passionnel, and the killer might have gotten off with a slap on the wrist.

Funny how the woman always ends up getting the short end of the stick.

Is that what happened here. Is that the missing piece of this morbid jigsaw puzzle. Maybe she had been going to Mr. Ecuador’s place, and this time they ended up at her place, and he blew up when she told him she was married and they couldn’t play in her yard because of her old man.

In fact, she is/was married, and her husband lives right here. Right down the hall. Three steps up and not more than ten paces down. Apartment 1C, to be precise. Does he know what has happened. The cops say he does not. Oh shit.

Is this going to be interesting.

Somebody who is not me is going to have to go down the hall and knock on the door, tell the husband what has transpired while he slept just feet away, and then walk him down the hall to take in the horrendous spectacle of his raped, dead, and partially nude wife, probably of many years, all in front of the wide-awake-at-5:00-a.m. gape of twenty-five neighborhood yentas staring through the lobby glass.

I would have covered her with a sheet, but the cops said that could interfere with evidence. For the husband, this is going to be agonizing no matter what, sheet or no sheet. I wish we had a couple more cops here to keep the nosy parkers back. This whole grotesque scene is about as bad as it gets.

Who am I kidding. If there’s one thing I’ve learned on the job, it’s that any call, anywhere, can always get worse.

I am standing about halfway down the hall between the vestibule and the victim’s apartment. I think I may have unconsciously moved here to get away from the crowd, if not the body. I’m quite sure I’ve seen enough for today. Lenny and I are just about to turn and leave when there’s an explosion of activity down the hallway in the direction of the apartment.

It’s dark in the hall but not dark enough not to see what may be one of the largest men I’ve ever laid eyes on barreling down the hall straight at me. It’s the husband, and he is very, very upset. Give me a second, buddy, I’ll be glad to get out of your way.

All I can think of is my National Geographic book Wild Animals of North America, which shows ancient cave dwellers being attacked by a giant cave bear, at least half again as big as a modern Kodiak bear. This man is channeling that bear.

I’m trying to flatten my back against the wall, the way the prisoners do in the movies, but I simply cannot get flat enough. He literally fills up the hall. I don’t think it matters what I do, because he has just enclosed my right forearm in a hand the size of a Polish ham. My God, what a grip. I’ve never felt anything like it. He’s dragging me down the hall with him. His hand is beginning to tighten and twist.

I’m pretty sure—I hope—he can’t twist my arm completely off. But not so sure he can’t dislocate my elbow or shoulder. From the feel of it, I could easily end up with spiral fractures of the radius and ulna. The kind of fractures abused children get. Maybe my bones are already too brittle for that. Maybe I’ll just get compound comminuted fractures. Mister, I’m not the guy. Please let me go. I’d yell at him, but I don’t want to piss him off. More.

For a second, I contemplate sticking him in the eye with my Parker T-Ball Jotter, until I realize the pen is in the hand attached to the arm which is now attached to him. Just as I give up this idea, one of the cops mounts him from behind. It’s the most absurd piggyback ride I’ve ever seen, but it does have the effect of getting Ursus spelaeus to relax his awesome grip long enough for me to wrestle free. With one cop on his back and another in his path, the husband begins to calm down enough to be walked to his wife’s body without further incident.

My arm looks like it has been pressed in the steamer at my uncle George’s dry-cleaning place.

What a raging beast. What a force of nature. What a monstrous, savage, ill-tempered man. Well, look at the circumstances. Look at his face. Look at his huge hands. Look at his knuckles.

Look at his knuckles.

Look at his wife’s face. It’s a matched set.

Maybe the young man from Ecuador is your killer, like everybody says. Then again, maybe not. Most people see Occam’s razor as a good reason, maybe even an excuse, not to look for more complicated solutions.

But what about looking for simpler ones.

The Park Is Good

Last year Dad was bugging me for weeks to let one of his customers at the gas station borrow my tent to go camping. I resisted, because I really didn’t want to lend it out. This tent was one of my few treasures, held over from my Scouting days, and I never let anybody else use it. It took me forever to save up enough money for it, and I kept it like new for nine years. It’s an Official Camper model tent with a roof that slopes from front to back and from the sides in front, to form a flat peak. The flap that you’d call the door is usually pitched taut to form a kind of awning. No floor—you have to bring your own drop cloth or air mattress or sleep on the cold, hard ground. It was a very simple tent, but I loved it.

It is now a year since I gave in and let Pop lend my tent to the customer, a kid I didn’t know, who returned it promptly after his trip. Last week I thought I might go camping again someday, so I opened up the tent to check it out. That damn kid had murdered my firstborn.

It was as if he had poured clay inside the bag and baked it. I literally had to chip away at the dried mud to even begin to lay the tent out flat, and when I did, I realized it was completely ruined.

To make matters worse, I discovered that the jerk who had borrowed it had taken it up to Woodstock, which of course I missed, because I was working. Nothing unusual about that. I am always working. The irony was almost too much to bear. The son of a bitch not only ruins one of my prized possessions but takes it to a concert I’d have given my left nut to attend.

Such is my life in summer. All work and no play. Makes Mike a dull boy.

Summer can be hard on kids in Queens or anywhere in the city, for that matter. Even the cheapest camps are outside the means of a lot of families, and the ones they could get into usually fill up way in advance. But city kids are resilient. They turn streets into arenas for all kinds of games. Stickball, kick the can, touch football. Every entryway with more than three steps is a venue for the eponymous stoopball. The side of any apartment building will do nice

ly for a pickup game of Chinese handball. Every patch of asphalt is a box-ball court.

And lucky is the kid who lives within walking or bike distance of a city park. These are pretty much the same all over New York. No frills. Functional and formulaic in design and execution. Lots of pavement and a high chain-link fence. Climbing over these fences when the parks are closed is a rite of passage everywhere in the city. Just like in West Side Story. Some things never change.

For the little kiddies there are areas with monkey bars, seesaws, large and small swings, slides, and painted hopscotch courts. Sometimes a self-propelled mini merry-go-round. For the bigger kids, there are b-ball hoops and walls for playing handball—with a pink Spaldeen of course.

Handball is my personal favorite. I myself didn’t know there was such a game as four-wall handball, played with a very hard nasty little black ball, until I went to college. I love it. It’s fast and furious, but Jesus, that ball hurts when you’re three feet from the wall and it comes bouncing off and smacks you right in the nose or the boy parts.

We’re on the way to one of these concrete summer camps in Corona right now. Apparently a kid has fallen on some glass, and he’s bleeding quite a bit. It’s unusual for a caller to provide this much information, and actually very helpful. Whoever called it in was smart. We didn’t get it as a rush, but because of the bleeding, Jose and I are moving a little faster than normal.

I can tell by the circle of kids this is the place. Also by the two police cars (where one is needed). It looks like some kind of day camp, but I don’t think it’s the Y or anything like that. Maybe a church group. No matching group T-shirts. There are a couple of counselors about my age and maybe thirty kids. The counselors do have matching tees that simply say COUNSELOR. One of the kids is sitting on the ground with a nasty gash across his knee. He’s bloody but seems alert, and the bleeding is more like oozing now.

The four cops and I are white. Jose is Hispanic. Everyone else is black. This could explain the two cars.

Things are racially tense everywhere in America this summer. Last summer. Every summer since I’ve been on the streets working for St. John’s. And long before that. But especially since they shot Martin Luther King Jr. two years ago.

This is Corona, on the border of East Elmhurst, Malcolm X’s old neighborhood. The police see Black Panthers on every corner, in every doorway, and behind every tree. They’re afraid. If they see more than a couple of black men together on the street, they get paranoid. They call for more cops.

The residents tend to overreact when they see the cops overreact, and so it goes. There’s always the possibility that all this overreacting can turn a simple call into a major event. When it’s hot, tempers flare everywhere. When two different racial or ethnic groups are involved, things can get very tense. Black and white today. Italian and Irish not all that long ago.

It’s hard on everyone. The tension. Earlier this summer we had a call not a block from here. A teenage kid was beating up on his parents, siblings, grandparents—anybody within arm’s reach. He and his family were black, so there was nothing racial going on at all, until six or seven police cars showed up.

One patrol car can draw a crowd in NYC. Half a dozen is mob bait.

And, of course, all the cops had to be white. And, of course, nobody in the crowd knew what was really going on, that the mom had dialed 911. That her son, all six feet six inches and two-hundred-fifty-plus pounds of him, was pummeling the hell out of his own family. A mob is a mob. They were black. They saw blue. They saw red.

This was a big, big, kid, and he seemed to know how to throw a punch and was not afraid in the least to throw one in the direction of any cop who was foolish enough to get in the way of one of his enormous fists. We were completely hemmed in at both ends of the block. Patrol cars had come in from both directions and so had onlookers. Mom was hysterical and had to be very conflicted. Yes, her son was pounding her family to pieces. But no, she didn’t want him hurt by the cops. The cops were hysterical and had to be very conflicted as well. Yes, we have to subdue this guy. No, we don’t want our jaws broken. Yes, we don’t want to hurt this kid in front of his mother and the neighbors. No, we don’t want to start a race riot.

No one in the crowd seemed at all conflicted. They wanted to see the cops the hell out of there or know the reason why.

As fate would have it, none of the policemen responding to this call looked very imposing. Appearances mean so much when you’re trying to keep things from escalating. Bluffing is as useful a skill on the street as it is in poker. I could see why they kept calling for backup. But it was pointless. Every new car that came brought more cops of the unthreatening variety. Nobody bigger than, say, five foot eight. Not that this is pathologically small for a cop or for anyone else. But it looks teeny when you’re confronted by a guy who’s six foot six.

Big Al and I were trying to keep on the fringe of things until we were needed. I wanted to see if any family members wanted help, after this kid had had his way with them.

But we were more or less locked in place. We had driven around the police cars and through the crowd to get close to the patient, and our ambulance now formed the center of a series of concentric rings: us, the kid, the family, the cops, and the crowd, which was slowly closing in. Hopefully not for the kill. Into the midst of this situation there came one more police car. It was unmarked. Out stepped four cops in uniform. The first three looked more or less like the cops that were already on the scene.

The fourth cop was the biggest man I have ever seen. Massive, with intense tangerine hair. Big Irish cop. Giant Irish cop. A throwback to the days when cops were cops and nobody but nobody fucked with them. It was Finn McCool himself, reincarnated in his own man-meat.

As this giant moved through the crowd, it parted for him as the Red Sea surely must have parted for Moses. He slid through it silently and effortlessly. A hot human knife passing through butter. Things got very quiet at the spectacle of this huge man making his way toward us. I wondered where they kept him between appearances. He wore sergeant’s stripes, so maybe he rode a desk back at the precinct. I wondered what they fed him.

He motioned to the officers, who now had their hands on the struggling-but-far-from-docile teenager, to bring him to the back of the ambulance. The kid was quieter now. The sight of the monster cop seemed to mesmerize him. Monster cop had the other cops back the kid up, between the ambulance doors, with his butt against the floor. Somehow, telepathically, he formed up the rest of his blue fraternity behind him to create a screen. He said something to the kid I couldn’t hear, and the kid yanked an arm free and punched Officer McCool in the face.

We all make our share of bad choices in life, but this one seemed particularly ill considered.

Finn slugged the kid and knocked him out like a light. The sound was not unlike that of a sack of cement hitting the pavement from a great height. And then they cuffed the young man, and we hauled him up into the ambulance, took a cop along for company, since the kid had just metamorphosed from kid to prisoner, and prepared to leave for EGH. Finn McCool got back in his squad car and returned to the precinct with the other cops, and the rest of the crowd just seemed to stand there and watch. Nobody said much of anything, as I recall.

I have no idea what effect this had on race relations that day in Corona. As I say, I’m pretty sure some of the players had mixed emotions. I guess the kid’s mom was grateful that her son wasn’t seriously hurt by the cops. Although I use seriously advisedly; it was a massive punch and could well have caused severe, unseen damage.

I guess the cops were grateful they got out of there intact. I doubt the crowd was satisfied. One thing we’d probably all agree on: it was something you don’t see every day. A giant appears out of the earth and subdues a mortal and then returns to his lair.

You could see how myths get started.

But today, it’s a very calm scene, as far from mythological as it gets. It’s hot today but shady and pleasant here in this pa

rk, and I should be feeling good except I feel bad. I’m sorry the kid is hurt. He’s such a nice little boy. I’d say he’s about eight or nine, and he’s trying not to cry, but I can see the streaks. Okay, my friend, let’s get you looked at by the doctor. All right, who’s coming with him, I say. The counselor by his side raises an index finger. It’s a combination of Yes, I’m going with him and Excuse me, I have a question. The question is, How will we get back here. It’s a good question. There’s no public transportation directly between here and Elmhurst General, and he says he doesn’t have cab fare. He himself could make the walk, but I don’t think it’s a good idea to ask the kid to, and he doesn’t either and says so. A wise decision for sure. I totally agree.

Without even thinking, I find myself telling him that we often go to and from EGH all day long, and if he and his charge are still there when we’ve dropped off our patient, we’ll drive them back, if we don’t have another call on deck. Why did I say that. I’m not sure we can do it. I know it’s against the rules. In fact, there are days we don’t go to Elmhurst at all. So it’s possible we won’t even see them for the rest of the day.

What excess of zeal is behind this spontaneous outburst. Am I trying to be a one-man ambassador for racial healing, or just trying to be a good guy, or am I yet another guilt-ridden white guy trying to be cool. I’m not sure. I’m not sorry I said it. I only hope that having said it, we can deliver. I’m staring at Jose, who says nothing but has that ball in your court, muchacho look on his face.

The counselor seems relieved, but I wonder what he really thinks. Is this ambulance guy trying to be a one-man ambassador for racial healing or just trying to be a good guy or yet another guilt-ridden white guy trying to be cool. We’ll just have to see how the day plays out.

As it happens, we’ve been back and forth to and from EGH more than usual today. Every time we go there, we have another call on deck. There is no possibility of driving the counselor or the kid back to the park when we have a call waiting. We can see the counselor and his small companion each time we drive in and out of Elmhurst’s yard. The boy has been checked out and is all bandaged up and ready to go home. We pass by them when we wheel a patient in and come out with an empty stretcher. The first few times we go by, I nod to the counselor, and he nods back. Jose puts the lights on when we’re off on another call. I think it’s so the counselor can see we’re tied up.

Bad Call

Bad Call