- Home

- Mike Scardino

Bad Call Page 19

Bad Call Read online

Page 19

After a few more calls, he just stares at us, expressionless. After that, he doesn’t look up when we go by.

We’re still going on calls, but I’m sure it looks to him like we’re never going to make good on our offer to give them a lift back. I realize it wasn’t a promise, but still. I hate to see them sitting there like that. Don’t they know anybody who can come and get them. I guess not.

It’s getting to be past suppertime, still quite light out, and we’re once again pulling into the yard at EGH. The counselor and the kid are still sitting where they’ve been since midmorning. Jesus, they must be starving by now. I wonder if they’ve even had anything to drink. Neither one of them looks at us as we wheel our patient into the Elmhurst ER. I won’t begin to speculate on what’s going through their minds.

But I’ll bet they’re not expecting what I’m going to say next.

Okay, men, let’s go. Let’s get you guys back to the park. Hop in. We could drop you off at home if you want.

It’s the first time all day we haven’t had a backup call out of EGH. They remain expressionless as we open the doors so they can climb in the back. Nobody says anything as we make our way back to the park. Then, The park is good, says the counselor. They only live right around the corner anyway.

When we open the doors to let them out at the park, the counselor grabs my right arm at the inner elbow. He looks me in the eye but says nothing. He squeezes my arm hard. Then he and his battered-but-brave little buddy walk away, and we mount up and ride off into the sunset. Literally, into the sunset.

What’s it all about, Alfie.

Am I really an overweening white man trying to be cool and/or prove I’m one of the good guys. Is this all for show. I know I can be cynical. Do I have to be cynical about this. Who did I do this for. Them or me. I have to stop overanalyzing things. I need to simplify my thoughts, reduce them to what I know that I know, for sure. And what is that, in twenty-five words or less.

I know I feel good about how today ended. That’s all I need to know.

Still Life with Prostitute

I love beauty. I love art. I never miss a chance to go to MoMA or the Metropolitan when I can. I love taking Barbara to the Met when she visits from Chicago and going to the Art Institute when I visit her there.

I hate ugliness. This is a big problem working on an ambulance in Elmhurst and in this part of Queens in general. Even though I was born in Elmhurst, not more than a few blocks from St. John’s, in fact, I have always hated its ugliness.

It’s as if a whole lot of immigrant people were thrown into this part of Queens and had to make the best of it with no thought of how it might look. It’s exactly like that, because that’s what happened. Frankly, I expected more, at least from Dad’s paesani, the ones responsible for the Renaissance. If form does ever follow function, here the function it follows is supporting survival long enough to make a few bucks and get out. And that’s just the architecture.

The form people’s lives take is equally disturbing, especially when their function is disrupted.

It goes without saying that the things we see every night and day on the ambulance are intrinsically ugly. Horrible things happen to people, and these things are ugly to look at, ugly to smell, ugly to touch, and ugly at 2:00 a.m. when you’re trying to sleep it all off and dream about things that aren’t ugly.

But it all has to be seen and smelled and touched. People need help when ugly things happen to them. And I do believe helping people is beautiful, if in a purely abstract way. People can’t help it when their bodies go bad on them. Or they’re injured. This is a kind of ugliness we will all experience, and it’s forgivable. Well, it’s not really a question of forgivable or not—there is no moral component; it’s purely nature’s way.

Sometimes I daydream about getting away from all of this and living my life in a beautiful place with beautiful people. In the meantime, I live here.

Occasionally, despite my best efforts to believe it doesn’t exist here, beauty comes out of nowhere and bites me in the ass. As much as I try to keep myself centered by clinging to my negative outlook. You can’t help looking up and seeing the sky, and it’s lovely—disarming—and you realize that it’s the same sky hanging over this ugly part of the city as over Oyster Bay or East Hampton.

We’re in a very—I mean exceptionally—ugly area of Long Island City right now on a man down call. It’s ugly to look at and also has an ugly soul. Lots of junkies here. Lots of hookers. Lots of junkie/hookers. And, of course, lots of sleazy visitors and hangers-on, who are always either selling something to the junkie/hookers or buying something from them. It’s getting uglier by the block. And the fact that it’s a sunny day and just about high noon doesn’t make it any prettier.

This is a really ramshackle address, a second-floor walk-up over some transmission-rebuilding business that looks like it has been closed for years. The windows are painted over, and I have no idea what’s going on inside, which is the point, I imagine.

I’ve been in a lot of beat-to-shit places. This has to be in the first or second percentile. There are no colors whatsoever inside the hallway. It’s all shades of gray. And black. No white—too filthy. At least one person has routinely moved his bowels in the hall next to the stairs. I wonder if he did it over the banister. You could end up with some serious splinters that way. Do us a favor, whoever you are: don’t call 911.

The cops are up here already and clearly not interested in hanging around one second more than is necessary to hand this off to us. They seem to feel it’s important to tell us that the man in the wheelchair is the patient and the woman with him was or still is a prostitute. The cops know her from days gone by.

The patient’s girlfriend or caretaker or common-law wife—or maybe just a friend—is doing all the talking. He seems too depressed to speak.

This man is named Karl, and he’s about fifty-five or sixty, she thinks, and has been in a wheelchair as long as she’s known him, which is at least the ten years he’s been living in this toilet. How he gets up and down the stairs is a story for another day. I’d say the lady friend is about the same age as Karl. She’s very fond of him; it’s not hard to tell. And protective. I guess she loves him, if you want to put a label on it. Well, there’s a little ray of beauty, shining down upon this awful scene.

It’s obvious there’s something very wrong with this man. There’s a lot wrong with him, actually. No doubt he’s an alcoholic. There are empty bottles everywhere, and he just has the look. The prominent blood vessels on his face give it the appearance of some kind of road map leading to nowhere.

Probably has diabetes as well. That’s most likely why he’s in the wheelchair. Cirrhosis, too.

I do know that I’ve never seen anyone with arms that look like his. It so happens that he’s wearing a sleeveless undershirt that leaves nothing to the imagination. Both his arms are totally black from shoulder to elbow and then more or less normal, if a bit blue, out to the hands. How his upper arms could be dead and his lower arms and hands still alive is beyond me, but that’s what I’m looking at. Last I heard was tissue death starts at the extremities and works its way back. Some blood must be getting through to his lower arms somehow, but apparently little of it is circulating in his uppers. At least not enough to do any good.

His lady friend comes over and takes me aside. It has taken her months and months to get Karl to agree to go to the doctor to get his arms looked at. It’s not that he has white-coat syndrome: she says he knows his arms will have to come off. Maybe not tomorrow but soon. And he can’t stand the thought of actually hearing them say what has to happen. Would the situation have been different if he had gone when she first started to ask him to go, she asks me. Really not possible to know, I say. But probably not, I add. Why not make her feel a little better about all this. Costs me nothing.

It turns out the patient is an artist—a painter—and she’s his biggest fan. Do you want to see some of his work. Okay, sure. She lifts up a drop clot

h, and there they are, canvas after canvas, propped against the wall. Dozens. It’s amazing work. He paints very much like Renoir to my eye, but they’re not attempts at forgeries or copies—it’s Renoir’s style but not his subject matter. The paintings are all from life. Karl’s life, which is quite different from Renoir’s.

There are cityscapes he has obviously done looking out his smeary window. Still lifes with empty booze bottles. Still lifes with full booze bottles. Still lifes with half-empty or half-full bottles, depending on your worldview. Well, as they say, you paint what you know.

There are portraits and nudes—hard to tell if his friend was the model. This is some seriously gorgeous stuff. More rays of beauty are shining down all around. But the reality of his position is sobering. It’s too bad, really. It would be nice to entertain the fantasy of a New York gallery owner or curator at MoMA or a Times critic discovering poor Karl’s work and giving all of this a Cinderella ending. That ain’t gonna happen.

I’m thinking about how his arms turned black. I can see him painting for hours in his cold room with his right arm extended and raised with a brush in the fingers, the blood pooling in his upper arm. He had to be freezing in here in the winter. The booze was almost certainly making him even colder and impeding his circulation. What about his left arm. Why is that the same as his right. Was he ambidextrous. Did he rest his left hand on the top of the canvas while he was painting. Or was it just his luck to be stricken in both his arms, to lose the use of the tools he needs to create his exceptional art.

I tell his friend that I’m impressed by Karl’s work, and it’s no act. She knows it isn’t. Street people can sniff out bullshit ten miles away, and it never pays to try to shine them on. Big Al and I are ready to very gently carry Karl in his wheelchair down the stairs out to the ambulance.

Do you want to come with Karl, I ask his friend. I don’t know her name and I should have asked, but now it’s too awkward for both of us. She does want to come. Fine. I help her in. I take a second to look at the squalor all around us. She seems to want to say something before I close the door and we start off. There are tears in her eyes as she speaks.

You know, she says, this is a beautiful man. This man paints like a dream. He’s a beautiful man.

That’s beauty enough even for me.

JFK

September 1970

I don’t like flying. For one thing, I’m afraid of heights. For another, I’m claustrophobic. Worst of all, I hate turbulence. I can’t stand jerky rides at amusement parks. The height plus the violent motion makes me freak out.

On my first airplane flight, in a Boeing 707, we hit some turbulence. I didn’t know if it was bad or not because, as I say, it was my first time. It was my good fortune to be sitting next to some guy going home on leave from the air force. He could see I was going nuts.

He struck up a conversation about flying and planes and turbulence.

I was certain he was going to tell me how this was perfectly normal and I shouldn’t worry and that aircraft were incredibly strong and overbuilt just to take turbulence many times greater than what we were experiencing now.

Instead, this asshole spent a good twenty minutes describing to me in horrific detail how planes such as the very one we were sitting in could break up just like that in turbulence just like this. He emphasized the words that and this like the word gotcha in a campfire ghost story. What a jackass. I’ve never forgotten what he told me about the structural weaknesses in various airframes, and to this day I can’t go through a turbulent patch without expecting to see a broken-off engine or hunk of wing go hurtling past my window.

I knew he was being a malicious son of a bitch. To get even, I asked him if he had been to Vietnam and did he see much action. He never said another word the whole flight. My guess—a clerk on a domestic US base and the nearest he’d been to real danger was being on the wrong side in a bar fight. I wish I could say I took some pleasure in this feeble attempt to lop off his manhood, but I was frankly too terrified to enjoy myself.

Some of these things are going through my head, these things about flying, as Pete and I are sitting in traffic, headed south on the Van Wyck, to a plane crash at JFK. I’m thinking about the pictures I’ve seen of crashes, of crash victims. About the horror of spiraling slowly from the sky and the certain knowledge of the death that’s coming up to meet you.

I try not to be afraid on this job, but it’s not always easy. There are things you see that no one at any age should have to see, ever, in their lives. I’m twenty-one right now, and I’ve seen too much already.

Sometimes I try to straighten myself out by thinking of kids in war-devastated countries, concentration camps, even combat. Things like that. There are unspeakable horrors I know I will never see, and I’m thankful for that. But the ones I’ve seen are enough for me. I do not believe anything positive ever comes out of seeing these things. Nothing. You might think you’d appreciate life more, but instead you’re more afraid of losing it. Of terrible things happening to people you love—or just people in general, even total strangers.

But it’s my job and I have to be professional about it. There’s no other option on the table.

Pete is being his usual dick self, playing that damn this is going to be the worst thing you’ve ever seen, kid game. Like that airman on my first flight. I can take pretty much, though. So far, I’ve been able to look at anything and not turn away. Anything. It does have its effects, though—not turning away.

The worst so far is not being able to sleep. Playing it all back at the end of the day. Day after day and night after night. And I have been drinking more than I used to. And I used to drink quite a lot.

I also don’t give a damn about much of anything, anymore, except marrying Barbara. I often wonder if I’ll ever be happy or even feel at ease again. I hope so.

Pete is pulling on and off the expressway, driving at crazy angles over the wet grassy slopes on the side of the road, just to get around a couple of cars at a time. I hope he doesn’t roll this hunk of junk. It’s so damn tall and tippy.

Traffic is backed up for miles. I have been in a lot of traffic jams on Long Island, and this is the worst by far. It’s a big call. I can hear sirens coming from every direction. Probably every available emergency vehicle on the west end of Long Island has been called for this—Emergency Services cops, firemen, fire rescue, the regular cops, and all the ambulances. When a passenger jet goes down, it’s a big deal. I can’t think of anything bigger.

This call is an ultra rush, but we’re not going anywhere fast. I wish Pete would lay off the siren. I wish they all would, out there. They’re nervous and excited. Doing this for a living doesn’t make you immune to the excitement, but it’s not a good kind of excitement. We need to calm down here. But Pete’s the big boss, and you don’t tell him to stop hitting the siren. He was having me hit it, but I guess he didn’t think I was going at it with enough gusto, so he took over. Go, man, go. See how it makes the cars just fly right out of our way while giving Mike a humongous migraine.

I have read of plane crashes with survivors, but those have to be the exception to the rule. You can’t win in one of these things; if the initial explosion or the impact from the fall doesn’t kill you, the fire on the ground will. It’s all very efficient and virtually inescapable.

I’m thinking about piles of charred bodies and cindered body parts littered all over the place, and I’m thinking this snail crawl to Kennedy is allowing me far too much time to think the thoughts I’m thinking, when, lo and behold, we’re here. We’re at an authorized-personnel-only entrance that opens right onto the field. There are police cars, ambulances, airport emergency vehicles, and fire trucks all over the place. It’s reminiscent of a Boy Scout camporee and might be downright festive, under very different circumstances.

A fireman in a black raincoat is motioning us in and pointing to where we need to park. As we pass him, he tells us to just stand by. Of course. What else are we going to do.

> Pete and I get out of the ambulance and start to walk toward the site. I’m struck by the sudden absence of his this is really going to be bad, kid crap, so I know for sure he’s as tense as I am. I suppose I could sit out this whole miserable event in the ambulance, if I want to. But you have to see something like this. I wish I could tell you why, but I don’t have the answer. It’s just something that has to play itself out.

And it is an awesome sight. It truly is. The earth is burned black for the diameter of at least a couple of football-field lengths, maybe more. The firemen won’t let us get too close, and there’s no need to, since they’re the ones who’ll be bringing out the bodies.

The huge, broken-up pieces of DC-8 are stunning to behold. We’re overshadowed by giant pieces of the tail and partial cylinders of the fuselage. There are a couple of engines on the ground and, farther back, the wing they came from. The whole thing looks like a gigantic suit of armor in which someone was burned at the stake. An enormous Joan of Arc comes to mind.

All the other pieces are too small and burned up for me to identify, except for a couple of charred seats and overnight bags.

Two guys from Queens General approach me and Pete and start to talk. They’ve been here awhile, since QGH is close to JFK and they were probably one of the first ambulances at the scene. I don’t know them, but I know that sometimes we all have to make conversation at a scene like this, to do what we can to normalize the situation and reduce the stress level. If Pete knows them, he’s not making any introductions.

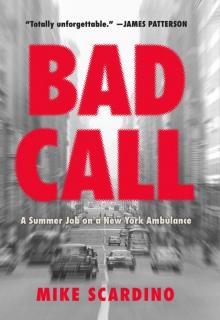

Bad Call

Bad Call