- Home

- Mike Scardino

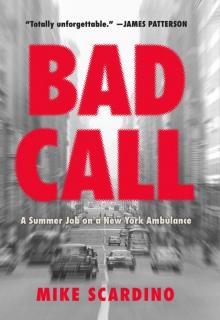

Bad Call Page 20

Bad Call Read online

Page 20

They’re telling Pete and me the story as they’ve heard it from someone who heard it from someone who might have been an alleged eyewitness. The jet took off normally but never got very far off the ground. It just flew down the runway at about a thirty-degree angle with wheels extended and flaps down, a few hundred feet in the air, and rolled over and touched the ground and started to disintegrate and exploded and burned. That was it.

One of the guys says he heard the tower people were saying that hunks of debris on the runway blew up from the jet wash of another plane taking off just before this one. He thinks maybe a piece of pavement or a blown tire or some other garbage from the runway had gotten stuck in the hydraulics of the flaps or something and prevented them from operating correctly. It sounds reasonable enough.

He says it was a charter ferry flight on its way to Dulles to pick up its fares and take them to Frankfurt and it had a crew of only ten or eleven on board. Only ten or eleven. Okay, that’s not as bad as one hundred fifty. But still.

The other Queens General guy says he doesn’t think it was fully fueled, since it would probably take on its full load of fuel in DC after it dropped off the crew members and before it was loaded with passengers.

Fully fueled or not, it caused quite a blaze. Just about everything in sight is burned to one degree or another, and a lot of it is still smoking.

Here come the firemen with the bodies.

I know what I expected to see, and so I’m stunned when I see they’re not really burned. They’re not really bodies, either, mostly parts. Impact with sharp aluminum pieces of the aircraft has literally torn them to pieces. The cuts are amazingly clean. Not what I expected at all. What I had expected were more or less intact crispy critters.

Here’s an apparently whole body in a body bag. The bag is not completely closed, and there’s a woman’s foot protruding from the open section. It’s a bare foot in a nylon stocking that’s torn just at the toe. Such a delicate tear for such a violent incident. As if it got snagged on a coffee table or something innocent like that.

It’s a beautiful foot. The toenails are painted light pink. I’m picturing the woman it belongs to; I know she must be pretty. Must have been pretty. This is one of the most pathetic things I’ve ever seen, this dead pretty woman’s pretty foot. It isn’t the least bit gory or disgusting. It is just so damn sad.

I can see her getting up and getting ready for this flight. Everything is completely normal. She’s taking a shower, making coffee, getting dressed. All of this is playing out as vividly in my imagination as if it were on film. I think she was probably living the life she wanted to live. I think she probably enjoyed her job.

I think she was not afraid of flying.

On a Day Like Today

I think a lot about luck since I started working on the ambulance. What it means and why things happen. Why some people get killed or maimed and others don’t, neither for any apparent reason. Why children have to die. I see people killed in the simplest household accidents and others survive the most horrendous calamities. You can’t know why.

Most people don’t even use the word luck right. They say you’re lucky if you have good luck or unlucky if you have bad luck. But, of course, it’s just luck either way. Luck is neutral, like nature.

Some of my hippie friends go on and on about nature, how great nature is, how beneficent, benign, and loving. The nurturing mother of us all. How what’s natural is best and we should all get back to it.

I know for certain, after taking this job, that nature doesn’t care about anything one way or the other. Things just happen, and that’s it. It’s ironic that the same people who think nature wants the best for us will then turn around and say things like Let nature take its course. As if that’s a good thing, even when it’s not.

I wish they could ride with us and meet some of the people who are pretty fucking grateful we are there so nature doesn’t take its course.

Then there’s God. Don’t get me started.

Luck. Nature. God. The Holy Trinity of mishegas. Whatever you choose to call it. Something out there/up there/around here is making things happen, and there isn’t a damn thing we can do about it, other than enjoy life when we can, hope for the best—and try to prepare for the worst.

Or at least try to duck the inevitable for as long as we can get away with it.

It’s a weekend morning in early autumn 1970, and I’ve been working for St. John’s since the beginning of the summer of 1967, the entire time I attended Vanderbilt, including Christmas vacations and since graduation in May of this year. One of these days I’ll be heading off for army basic training, but as of today, I still haven’t heard when. But I have heard that even though it’s the National Guard, it’s possible we may be activated and sent right to Vietnam. It’s all feeling like a bad dream I’m never going to wake up from.

In the meantime, I can’t get a real job. Or an apartment. Or married. Barbara is back in Chicago, in graduate school at Northwestern. She hates it. We just want to get married and run away somewhere. Any damn where. We both feel like a couple of flies caught in amber.

I can’t say how many calls I’ve been on. It could be thousands.

This job has made me harder about some things and more terrified about others. I just cannot come to grips with the reality of death. Who can. I haven’t developed the least degree of immunity against the fears we all share. If anything, my fears may have a bit more dimension than other people’s now. Otherwise, they’re basically the same.

It’s a beautiful day today, but that doesn’t keep me from my usual introverted regimen of self-pity, doubt, fear about the future, and free-ranging dysphoria. I think I have learned the trick of letting pain and pleasure coexist, though. No reason I can’t feel bad and pretend to enjoy this wonderful day at the same time. Who’s going to know but me.

It’s been hot and muggy lately, but today is cool and dry. This is the kind of day when you see lots of cars broken down by the side of the road, with white smoke billowing out from under the hood. Something about the thermostats. They always seem to go crazy when the seasons change. Dad explained to me once how they could get stuck, but it went in one ear and out the other. Anyway, it happens.

It’s almost like the cars can’t deal with the nicer weather and something inside of them just pops.

Fred and I are on the way to a possible DOA on the street in Forest Hills. What a shame to die on a day like this. But ask yourself: What would be a good day. Imagine if you had to pick your day to die. Or even just knowing the day. Who could live with that.

One of my Jewish friends from Bayside High School once shared with me a riddle from the Talmud. What day should you atone for your sins, he asked. I shrugged. The day before you die, he replied. Without a moment’s hesitation, I laughed and said, How the hell are you supposed to know when that is, and almost before I could finish I realized what a dumb question that was. I walked right into it. My friend just smiled. A little smugly, but it was okay. Anyway, I got the point. You will almost certainly not see it coming, so you’d better be ready right now. As ready as you can be.

There are a lot of people here on the street for this hour of the morning. The cops are telling us that it’s all one family. Big family. Apparently they were out for a stroll, and the family patriarch just dropped dead on the sidewalk. I have had a look at him, and he is indeed dead. Everyone is very upset but not hysterical. One of the women turns to me and asks, Why did he have to die on such a beautiful day. Jesus, was I thinking out loud.

I don’t think it has been more than a couple of hours since our Forest Hills DOA on the street. We get another call. It’s another possible DOA. Also on the street. Also in Forest Hills. Not more than a block from the first.

It’s a carbon copy of the first call. Large family. Dead patriarch. Almost certainly a heart attack or stroke or something quick and clean like that. Same trip to the morgue. Similar remarks about the irony of the bitterness of death contrasted against

the blissfulness of the day. I don’t know about Fred, but I’m getting a little creeped out. But I’ll take creeped out over depressed any day.

We barely have had time to get into 434 after leaving our latest passenger at the morgue when another call comes in. Do I even have to say what it is at this point.

I’m starting to think about luck again.

What are the odds that something like this—the death of three men out walking with their loving families on a perfect day—could happen within hours of one another, in almost exactly the same spot. Did their thermostats pop because of the nice weather.

Did Mother Nature decide she wanted them back at this precise instant in time.

Or did God harvest this crop at the moment of perfect ripeness, when these men’s lives couldn’t possibly get any better. Only worse. When there was not one single thing left to gain by staying a minute longer.

This is a lot to take in. I think I’m going to be thinking about it for a long time.

Like the rest of my life.

A Cold Day in Hell

January 1971

I’m on my way to say goodbye to whoever is around in the ER at St. John’s. In a couple of days I’ll be on an Eastern flight out of La Guardia on my way to Columbia, South Carolina, to start basic training at Fort Jackson. And assuming nothing horrible happens between now and August, Barbara and I are going to be married.

I should be glad that this whole ambulance thing is finally—hopefully—going to end. And I am.

But I’m not that keen on what the coming six months will bring. How many clichés can I cram into the next few thoughts. Out of the frying pan. The devil you know. Be careful what you wish for. Three are enough, I guess. That more than covers it.

Anyway, how bad could it be.

It’s freezing cold today. In the low twenties. I’ve been working for St. John’s since the beginning of the summer of 1967. All of the summers and the winter holidays since I started Vanderbilt. I escaped working Thanksgivings and Easters by staying at school. School was my great refuge from St. John’s. After sophomore year, I barely went to class at all. No wonder I almost flunked out. Thank God Barbara took such great notes.

This last stretch was the worst. From graduation last May until only a few weeks ago they’d never tell me when I was going to start basic. Is there anything worse than an open-ended jail sentence. You want to start your life, and it’s not possible. And now it’s going to be delayed another six months. I hope I can find a job when I get back from South Carolina. Not on St. John’s Queens ambulance. Although I guess they’d be happy to have me back. What a comfort. Always good to know one has options.

What do I have to show for it all, I wonder. All those calls. All the grief and the lost sleep and the isolation and the tears. All the horror. The Horror. Queens Boulevard was the river. But there was no Kurtz to find, no destination, just the cruising: up and down the river and deep into all the tributaries along the way.

What do I have to show for it. Seriously now. No student debt, for one thing. I was well paid, I must admit. I can’t come up with anything else. The job did nothing to advance my foredoomed career in medicine. That self-aborted virtually on day one.

Did it make me understand more about life, other than how bad it can be. How could it. If anything, life is more an enigma to me now than I ever imagined it could be, at least at my age. I would have thought that coming to realize the imponderability of existence was one of the many unfortunate perks of old age. You come to the end of the road and you realize you don’t really know anything. How silly to think you would. Is it wisdom to realize you’re actually silly, after all.

At least I know it now and don’t have to be disappointed down the road, assuming I get there.

I’m a lot more fearful than I was before I started. Why. That’s easy: I know what can happen. I have seen it again and again and again. You want to talk fragile; that’s what we are. Life’s brief candle. It sounds so lyrical when you scan it in Shakespeare. In real life, it’s scary as hell to see how thin the membrane is between being and nothing.

So what do I have to show for it. Nothing. That’s it. Not a thing. Nothing that actually shows. Try to picture that. What does nothing look like.

When Siddhārtha experienced his four sights, at least he ended up enlightened. I imagine the best I’ll do is learning to stop asking questions that have no answers.

I do have a few visible mementos. A civil defense armband. A toe tag I carry in my wallet as a conversation piece. No photos, except for a self-portrait I shot sitting in 434. This was on a day I had decided I’d start my great photo-essay of life and death on the ambulance. Like Gene Smith’s “Country Doctor” photo-essay for Life. This would be my big start as a photojournalist. This might make it all worthwhile.

What the hell could I have been thinking. Not only would this have been illegal. It would have been immoral. It’s bad enough to be present when the worst things happen. It’s bad enough to have to see these things with your own eyes and feel them in your stomach and your heart. To intrude on the grief of the bereaved. No need to capture them on film. Flip over a Gene Smith, and you’ll find a Weegee. It would be too easy for that to happen.

With those thoughts in mind, I put my camera away and never brought it again.

I also have this jacket I’m wearing today, an official St. John’s ambulance jacket. I could have worn my regular coat, but I thought it would be nice to wear this one, as kind of a goodbye gesture. Shows I’m on the team, rah, rah. It was a gift from Eddie the first time I worked over Christmas. A hand-me-down. You have to buy these jackets with your own money, so it was his to give and not the property of the hospital. It’s still like new, blood-red nylon on the inside and dark blue outside, with some token synthetic insulation in between. I’ve often thought it would be more practical if it had the red on the outside.

There is a colorful ambulance patch on the shoulder and lots of pockets for pens and other handy junk, like the foil-wrapped alcohol prep pads I always take along to clean up my hands and the little jaw wedges we carry for seizure patients so they don’t bite their tongues: two tongue depressors with gauze wrapped around and in between, all bound up with adhesive tape. Quite effective if not all that sanitary after being in your pocket for a few days. When they got dirty, we made new ones. They were absorbing to make. On a slow day we’d be out constructing them in the ambulance yard, like a bunch of overgrown campers making lanyards. I have used these on many occasions. They work.

I like this jacket, even though it has no vents and the nylon makes you sweat like a pig when you’re working. You end up so wet underneath that you don’t dare take it off, even indoors, or you’d freeze your butt off.

Everybody’s out on calls when I get to St. John’s. Everybody I wanted to see. Everybody but Pete, of course. Truly the last person I wanted to see. He’s at the reception desk when I walk in, and he doesn’t look up, even though he knows I’m standing here. What a puss on. Like he bit into a chocolate-covered turd, minus the chocolate. Now he’s looking up at me like Yeah, what. He’s just staring at me.

No, hold that thought. He’s staring at my coat.

Gimme the coat, kid. Kid. It’s down to that. I’ve been here since 1967. I wasn’t even legal to work here when I started. They employed me illegally for more than three years. I’ve gone on thousands of calls. I’ve been there when he’s needed me. I’ve done as good a job as I could without going psycho or turning corrupt. My nerves are totally shot. And it’s down to Gimme the coat, kid.

Nice guy.

I tell him Eddie gave me this coat. It was Eddie’s coat. He bought it. He could have thrown it out, but he gave it to me.

No, no, no, kid. That coat belongs to St. John’s. I need it for the new guy. So that’s it. Make way for the fresh meat.

Pete, it’s freezing outside, I say. Let me leave it with Pop and he’ll give it back when you gas up.

No, I need it right now. Lemme have it.

God, is that tempting.

The ER is full of people, and they’re hearing all of this. I wonder what they’re thinking. There’s no one here from the hospital who can intervene. No one who outranks Pete. Hey, I’m in the union, 1199. I pay my dues. Where’s the damn rep when you need him.

For a very brief moment, I contemplate slugging Pete. I know I could do some damage, maybe knock him down—maybe even out. If I were arrested, I wouldn’t have to go to Fort Jackson. If I were convicted, they’d kick me out of the National Guard for sure. There’s a definite upside to the slug option.

There’s a downside, too. Jail and a felony record. I’ll pass.

In one motion I take off the jacket and throw it in Pete’s face with a hearty Fuck you, you fucking piece of shit, the words resounding all too clearly in the dead-silent emergency room.

The jacket probably weighs less than a pound or maybe two. It’s like throwing a bath towel at someone, but the effect is far better than any possible punch I could have thrown. Pete looks like he stuck his finger in an outlet. He’s in total shock. I think he knows how close I came to getting physical. And in front of all these people. He’s a proud man, and proud men are most vulnerable in their pride. I couldn’t have hurt him as much if I had slugged him with all my might.

He lunges at me with the jacket in one hand and an index finger aimed straight at my nose. I have to force myself not to blink. You will never, ever work here again, he roars. You got that, kid. I am going upstairs right now and filing an incident report that will go on your record. I promise you, you can forget about working for St. John’s. FOREVER.

Is that a promise. Do you promise I’ll forget about:

The Forest Hills woman who woke up with a rat eating her nose

Bad Call

Bad Call